Of all the problems confronting a critic, perhaps none is as confounding as attempting to describe an animated motion picture that breaks new aesthetic ground -- for the most audacious and breathtaking examples transcend the very limitations of words. The Painting -- a staggering feature by Frenchman Jean-François Laguionie -- raises that maxim to a whole new level. In addition to a narrative that is rife to bursting with conceptual invention, its images defy description. This isn't a movie; it's a visual smorgasbord, a 76-minute intoxication of the senses.

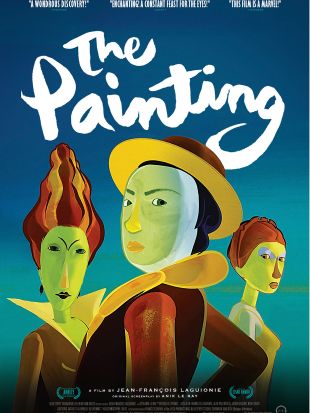

The story rests on an inspired conceit: What would happen, Laguionie asks, if each tableau on an artist's wall somehow encompassed its own miniature world, subject to its own rules and laws and occupied by its own population? At the outset of the story, we travel inside one such painting, a kind of medieval sphere inhabited by three "species" -- the Allduns, a series of characters completely finished by the creator, who have all of their colors intact; the Halfies, subjects half finished, who long for the strokes of a brush that will bring them to 100%; and the Sketchies, crude and frail charcoal sketches who began as conceptual ideas and remained at that level. Within this realm, a three-tiered class system has developed -- the Allduns are pompous, supercilious wealthmongers who live a ritzy life in a castle-like setting, treating the Halfies as social outcasts and the forest-dwelling Sketchies as disgusting, repulsive vermin. A tale of verboten love emerges from this environment between the Alldun boy Ramo and the Halfie girl Claire.

If this sounds like the setup for a series of clichés -- a thinly veiled parable about racism, for example, or a +Romeo and Juliet clone -- rest assured that the story does not end there. It takes a dazzling and unforeseeable turn when several of the characters venture out into the "real world" of the artist's studio and begin to explore the microcosms of neighboring paintings. It is here that the breadth of Laguionie's imagination fully takes hold, with fascinating pontifications about the notions of reality and existence within the onscreen world (and the worlds within that world), which, of course, parallel the existential enigmas at the heart of our actual human experience.

One of the sneakiest aspects of the movie manifests itself at this stage: In lieu of witnessing a hundred disparate artistic styles represented in the workshop, we get numerous slight variations of the same style applied to a whole host of themed canvases -- which makes more sense conceptually because one artist is responsible for all of these creations. Laguionie interpolates everything from trippy abstraction (in dream sequences involving Claire, frightening plants, a leaf bed, and an enormous eye) to at least one image that recalls old European newsreels (silhouetted toy soldiers marching in formation); all of the aesthetic variations on display here -- and there are too many to count -- are delightful.

Curiously, though the movie is enormously satisfying and children would love some individual passages of it, it isn't really suitable for kids. For one thing, it's too heady and contemplative for small fries; the closest mainstream animated equivalent might be Ratatouille, with its meditations on an artist's need to create, but The Painting's philosophical musings have far more in common with movies that lie well outside the confines of Hollywood -- such as John David Wilson's Shinbone Alley or Bruno Bozzetto's 1976 Allegro Non Troppo. The content of The Painting is also a shade too objectionable to really qualify it as family fare; for instance, we get scary sequences involving a scythe-wielding Grim Reaper and a tentacled Chinese dragon-like monster who chases an animated little boy through the streets of Venice, an abstract montage that visually demonstrates male/female union through intercourse, and an extended scene in which a nude woman in a painting converses with the lead characters, bare breasts in full view.

On every level, The Painting reminds us that the most exciting animated work is emerging beyond U.S. shores. Pixar films may be excellent commercial product with superb artistry on display, but when held up to the Laguionie movie, they prove that even a 200-million-dollar budget cannot always guarantee the broadest and deepest imagination available to a filmmaker; they have also never dared to take the kind of stylistic and narrative risks quite as extreme as the ones that Laguionie incorporates here. In a fair and just world, The Painting would be a shoo-in for Best Animated Feature at Oscar time, or at least a strong contender. That seems highly unlikely given the hegemony of Hollywood animated pictures, and it's shameful, for the film merits that level of honor and recognition.