In the early 21st century, Scott Walker was known -- by those who were still aware of him (who included David Bowie, also the executive producer of this movie) -- as one of the most enigmatic music stars to come out of mid-'60s England. Except, of course, that he didn't come out of mid-'60s England but late-'50s America; and his name wasn't "Walker," but Scott Engel (or, legally, Noel Scott Engel), among other little-remembered oddities about him. But his strangest and most compelling attribute, apart from a baritone that made Bill Medley of the Righteous Brothers sound like an adenoidal teen, was his mix of musical creativity and the personal and professional reclusiveness that had characterized his career since the early '70s. That wall of mystery was breached in 2006 when Walker allowed filmmaker Stephen Kijak into the studio to profile the artist, in connection with the release of his new album, The Drift.

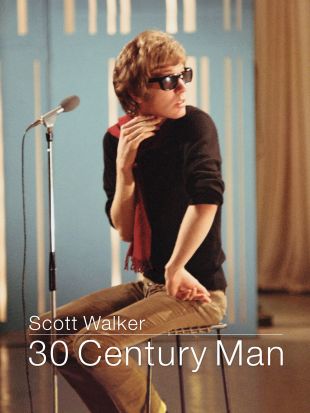

The result is a movie nearly as enigmatic as its subject. We start with visions of Walker from his days as Scott Engel, except that these are just glimpses, and for the first quarter of the documentary, apart from the singing voice (in the Walker Brothers and immediately after) and snatches of old songs, his image is mostly seen in grainy film clips and newspaper photos, while Walker in the here and now is seen, at first, with a cap pulled down low over his head, collar up, and mostly turned away from whatever camera is pointed toward him. After some teasing segments, we do, indeed, see Walker full face -- time has been kind to him, given his 50 years or thereabouts in music -- and simultaneously we plunge into the whirlwind that pop stardom became for him, as Scott Engel joins the Walker Brothers who, as a trio (with Scott not as lead singer but as a backup singer), make their way to England and success. The movie is very generous in the credit it gives to producer John Franz and arrangers Ivor Raymonde and Angela Morley (formerly Wally Stott), though there's no mention (that this reviewer can recall) made of vocal coach Freddie Winrose, who played a key role in Walker's transformation into a solo artist.

One discovers an artist who seemed to have aspired to stardom while barely into his teens, only to have it thrust upon him suddenly, and very personally, through a side door -- when he was elevated to lead singer on one song, which became a monster hit. And having had stardom dropped in his lap through happenstance, Walker seems to have spent the rest of his life and career bent on taking back control of that role completely in his own terms, first by staking out his claim on unique repertory, through the music of Jacques Brel; and, increasingly, by composing his own repertory, a process through which he integrated elements of classical music from across several centuries. All of this is fascinating, but proves much more compelling in the listening (to the resulting music, as presented on the soundtrack) than in the visual telling. Kijak makes a valiant effort, and his interviews -- with Walker and longtime fans and admirers such as Bowie, Brian Eno, and '60s pop/rock icon Lulu -- are interesting enough. But in Scott Walker, one is dealing with a subject who doesn't concertize and hasn't been in front of too many still cameras, much less television or movie cameras on a regular basis since the 1970s -- and by that time, when he was seen on camera, it was often as a still, solitary, moody figure, a kind of musical analog to a brooding James Dean or Marlon Brando, two decades or more removed. So we're not talking about one of the more visually stimulating subjects in music, and the performance clips that do exist and are used end up depicting a solitary, isolated figure, even to some extent when he was seen working within the context of the Walker Brothers.

The resulting movie tends to be made up of lots of talking heads, shots of newspaper articles and photos from the 1960s, brief performance clips and publicity shots, plus one dedicated fan showing off memorabilia which -- as it is in color (as is his sequence) -- tends to be a sharp, but ultimately digressive, contrast to the subject's own history. This wouldn't matter so much if the new recording around which the movie is hooked, The Drift, were a little more accessible. But it isn't -- this reviewer heard it at the time of release and found it interesting but ultimately repellant (which is, of course, a matter of taste). Also, the portions of the recording heard in the movie are no more attractive than they were as a pure listening experience. In the broader context of artistic endeavor, Scott Walker is welcome to make whatever music he likes, and if someone doesn't like it that's just too bad for both parties -- but it compounds the movie's problems that it does lead to such as inaccessible end point, if not an actual dead end. Given the nature of his subject, Kijak has actually done a fine job, getting the movie that he has gotten out of Scott Walker. One longs for an additional performance clip or two -- sad to say, some of the highest quality video of Walker in action in his solo prime was destroyed when the BBC junked his variety show, and only stills survive from the program -- or perhaps one additional song or two on the soundtrack to liven that side of things up. But all of that said, most of the 96 minutes of movie here will hold one's interest, better than one could have anticipated, on the strength of the music and the enigma behind it. It's just that it doesn't get you too much closer to nature of the mystery at its center that is Scott Walker, so much as placing that mystery in context within a larger pop-culture map.