At its core, Adam Elliot's stop-motion animated opus Mary & Max may well be one of the most despairing mainstream features ever made. That isn't intended as a criticism of the film, but as an observation; despair is integral to the film's worldview. In Elliot's universe - a godless, a-humanist universe of chaos, random violence and meaningless, tragic absurdities - humans create their only real significance via intimate personal connections with one another. The earnestness of one such connection - a marvelous friendship at the center of this story - also gives the movie resounding levels of heart, soul, and hope, that effectively offset the maelstrom of suffering it perceives.

The story, which Elliot loosely adapted from one of his personal experiences, concerns Mary Daisy Dinkle (voiced as a child by Bethany Whitmore and as an adult by Toni Collette), a lonely, sad, bespectacled 8-year-old growing up in suburban Australia in the late 1970s. Saddled with an outrageously dysfunctional family - mother Vera (Renee Geyer) is a chain-smoking hag in granny glasses who drowns herself in sherry on a regular basis, while absentee father Noel works in a dehumanizing job at a teabag factory and bides his time stuffing the carcasses of oscine roadkill -- Mary longs for a real friend. She finds one by randomly picking a name out of the New York City phone book, and a short letter later, snags the most random of pen pals: Max Jerry Horowitz (voiced by Philip Seymour Hoffman). He's a sad-sack, overweight loser in his mid-40s, saddled with a history of random occupations, that include issuing subway tokens and working in a condom factory. Max, like Mary, has no friends, no loving and supportive family; his evenings consist of devouring prodigious numbers of chocolate hot dogs and attending Overeaters Anonymous meetings, where he is relentlessly accosted by a grotesque, overweight, lovelorn woman. As the years and decades roll on, Mary and Max become best friends despite the vast geographic separation between them, and spend their exchanges confessing their most intimate secrets and emotionally affecting experiences with one another.

Elliot has compared this film to Alexander Payne's About Schmidt; it has the same conceit of a zero pouring his heart and soul out to a distant friend, but this is a far darker and angrier movie. The world we're presented with is unforgettable, especially for the thematic precedents it sets in animation. The director covers such areas as alcoholism, suicide, racism (the Jewish Max has traumatizing flashbacks of anti-Semitic bullying from his childhood), homelessness, electro-shock therapy, institutionalization, clinical depression and chronic loneliness. It would be devastating if the writer-director-animator didn't counterbalance the grief with the sweetness of the central relationship, or supplement the material with a marvelously wacky, way-offbeat sense of humor and visual magic that work in tandem and overwhelm the viewer. The genius lies in thousands of wondrous details and narrative developments, with sequences so finely embroidered that Elliot must certainly have spent an unholy amount of time pouring over the minutiae of each scene and character and lacing them with the inspired. The instances are almost too innumerable to mention, but two of the movie's finest moments (and biggest laughs) arrive courtesy of Max's neighbor Ivy, a prune-faced woman whose legal blindness doesn't prevent her from making Max inedible bowls of soup, and Max's pal Mister Alfonso Ravioli, who grows addicted to self-help books and finally decides to make good on his ambition to leave Max and explore the world - making Max perhaps the only individual in history to be socially abandoned by an imaginary friend. On many other occasions, Elliot tosses in throwaway gags and bits that earn a fair number of belly laughs, such as the sight that follows the disclosure of Asperger-ridden Max's inclination to take things too literally (Elliot cuts to him actually taking a seat along with him on the bus), or the sight of Mary (when she attends college as a psychology major) reading a book entitled, 'I'm Okay, You're A Homicidal Maniac.'

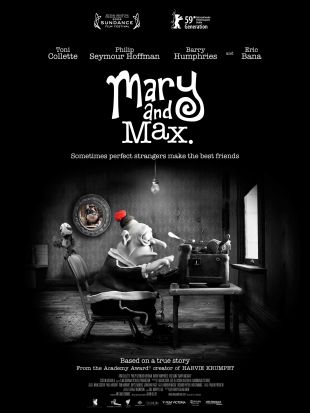

It perhaps goes without saying, as well, (given Elliot's track record) that the characters are beautifully and meticulously rendered and animated, especially their facial expressions; they often verge on the adorable, but that works beautifully here, because it offsets the gallows humor and cruelty of many of the narrative developments.

On many levels (including an identical tone and voice, and similar character designs) the film recalls the genius of Elliot's prior effort, the 30-minute Sundance Festival darling Harvie Krumpet (2003); this represents a step forward, however. Whereas Harvie, though immensely enjoyable and occasionally brilliant, seemed at best like a collection of random absurdist sketches, loosely linked by the thread of a single character, Mary & Max has a purpose for being, rooted in the aforementioned theme of spiritual and emotional salvation through connectedness with other human beings. One may or may not agree with Elliot's agnostic existentialism, but the film defies one to not feel swept up in the emotional undercurrents of the central friendship - to such a degree that when the final scene arrives, with a revelation of Mary's significance to Max, the story succeeds at touching one's heart on a deeper level than we might ever have imagined possible.