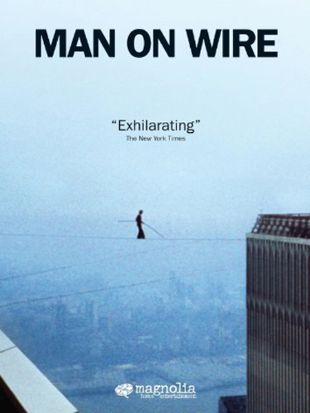

Back in the late '90s, a heartbreaking incident occurred involving a young American college student that made headlines in some local papers. In an attempt to win a "dare" with some of his friends, he made the hare-brained (and impetuous) decision to scale a radio tower atop a university building. The rungs were wet from rain, and he slipped off and fell to his immediate death -- a humiliating end, to be certain. The contrast between the circumstances surrounding that tragedy and those surrounding Frenchman Philippe Petit's now-famous August 1974 feat -- a 45-minute walk on a tightrope suspended between the tops of the two World Trade Center towers -- illustrates the central thesis of director James Marsh's magnificently entertaining new documentary about the Petit stunt, Man on Wire, which deservedly picked up two of the top prizes at Sundance in January.

Unlike the aforementioned student (and the ill-fated victims of many other dangerous stunts over the years) Petit perceived tightrope walking as his form of lifelong creative expression, and spent an unholy number of hours, weeks, months, and years perfecting his craft. Such actions saved him by making the Trade Center feat about a thousand times safer than it would have otherwise been. Everything leading up to Petit's Trade Center walk echoes his explicit comparison of himself to a master artist -- the preparatory details suggest the image of a sculptor gradually honing in on a creation from a formless block of clay. From there, the film expands the breadth and ambition of its ideas and begins to turn around the same profound theme as Ratatouille -- that every artist (performance or otherwise) requires the breadth of freedom necessary for self-expression, though that freedom will invariably pose risks to oneself. After all, what is any work of art except for the creator putting his or her deepest and innermost self "on the line" for the world to see, and thus risking humiliation? Undergirding these ideas, Marsh paints a portrait of unbridled determination, courage, and raw intelligence in Petit that shows him implicitly damning all the naysayers by thinking everything through with an almost obscene level of thoroughness. The director intuitively affords so much attention and screen time to the scientific preparations behind Petit's coup that the film at times threatens to turn into a catalogue of detail. We learn that Petit made a photographic record of the prospective mounts to which his cable could be affixed on both towers; that he considered, gauged, and compensated for possible torque on the cable by anchoring it with diagonal mounts attached to the central line; that he and a friend devised a method of mounting the line between buildings by firing an arrow attached to the cable from one building to the other; and so on, and so forth.

The director approaches this material like a first-rate thriller, employing a largely chronological narrative structure that ratchets up the tension (despite the known outcome) as the film details Petit's efforts to pull a band of international assistants together, and as those men spend time onscreen reflecting on the crafty, incredible ways in which they thwarted Twin Towers security and the New York Port Authority in carrying out their "artistic crime." Marsh is abetted throughout by the thoroughly winning presence of middle-aged Petit, a natural showman, who turns up on-camera for interview commentary, and who imparts a wealth of emotion with his excited, impassioned recollections. In addition to suspense, the film also benefits enormously from the inclusion of offbeat humor throughout, such as the revelation that one of Petit's cohorts was a terminal pothead (who showed up for the preparations stoned), and the revelation that Petit celebrated his success on the wire with a series of actions that completely ignored the devotions of his longtime girlfriend -- he accompanied a groupie to a nearby hotel and indulged in uninhibited sex with her (an event recreated in hilarious black-and-white flashbacks). Equally funny are the authorities' irritated reactions to Petit's wire stunt, which Marsh wisely holds off-camera until about ten minutes into the photomontage depiction of the actual walk. It may have been inevitable that Marsh needed to work in dramatic reenactments of the preparations with actors playing the perpetrators' younger selves, but the dividing line between the period footage of Petit and friends and the footage of the actors is invisible. The young actors bear such an astonishing resemblance to their real-life counterparts that it looks like Petit actually had people shooting sound footage of him over the years, while he planned the coup, conducted brainstorming sessions with his cohorts, mounted a "test" wire in his backyard, and perfected his walk.

Especially in the wake of 9/11, the film's lengthy Super-8 sequences of the World Trade Center towers in mid-construction (which blanket the first ten minutes of screen time) bring a poignant, elegiac quality to the material. The documentary benefits from this added level of emotional complexity, and it in no way detracts from the suspense or the humor in the sequences surrounding it. The film's only real lapses are twofold: it goes on a bit too long, lagging somewhat at the midway point, and when we actually reach Petit's much-anticipated derring-do atop the Twin Towers, Marsh fails to incorporate an actual film of his walk, resorting (as mentioned) to still photographs. It may be true that such footage doesn't exist -- that the actual walk was impossible to catch on camera (back in 1974) given the clandestine circumstances of the preparation and planning, and the height of the buildings. (The tale made city-wide and national headlines and drew massive crowds -- didn't news cameras, arriving at the Trade Center, at least attempt to capture some of it?) If not, that's a serious handicap for Marsh to work around, though we do get incredibly entertaining film clips of Petit pulling his high-wire stunt at Notre Dame Cathedral and the Sydney Harbor Bridge. Anyway, on some level, one could argue that the absence of an actual filmed record of the Twin Towers walk further ensconces the feat itself in an aura of myth and legend -- the sorts of myths and legends that explicit onscreen depiction can easily destroy.