Michelangelo Frammartino's pseudo-documentary The Four Times (Le Quattro Volte) embodies the latest example of what might be termed "cinematic eclogues" -- highly poetic pastorally themed works that visually meditate on the connection between the land and its people. The parallels to the ancient Roman poems are particularly strong in this instance given the center-stage placement of a contemporary shepherd. We've witnessed a pursuit of comparable Virgilian goals in other recent films -- some triumphant (as in Salvatore Mereu's 2008 Sonetàula) and some unequivocally disastrous (as in Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash's 2009 Sweetgrass). Le Quattro Volte falls somewhere in between. It isn't a complete success, but (unlike Sweetgrass) it isn't boring, either -- and it contains a middle passage of such startling emotional power that it does merit some recognition.

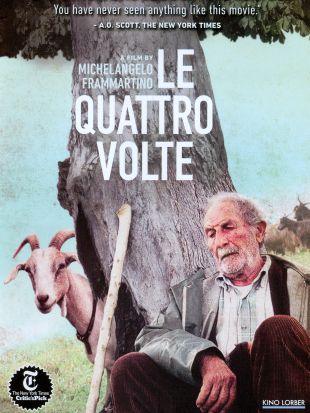

The entire movie unfolds in the village of Calabria, in south-central Italy. A pre-credit sequence features close-ups of a black domed structure punctured with tiny holes that emits curls of smoke from its pores. We sense that some mysterious geological process is occurring inside, though Frammartino deliberately fails to elaborate -- leaving the image elliptical, mysterious. The director then moves into intimate daily observations of an unnamed aging Calabrian shepherd who routinely leads goat herds and a sheepdog through the nearby countryside in the days just prior to his death.

The passages surrounding the shepherd are utterly spellbinding. For ten or 15 minutes, the movie works to hold our attention, yet we quickly settle into its drowsy pace and narrow our gaze to its level of observation. In fact, Frammartino manages to do something excruciatingly difficult that the Hungarian director Béla Tarr has long striven for and so often accomplished: he leads the audience into a uniquely paced mindset -- a gentle pastoral lap -- and we find our perspective unified with that of the shepherd.

The film also succeeds beautifully in the passages surrounding the shepherd's death. The animals somehow sense the old man's passing and come to their master's aid. It would be unfair to reveal more here, but the events pull us in and hold us; scenes that might easily grow too cute in other hands (with the anthropomorphization of animals) take on a haunting, almost mythical, resonance. This extends to a subplot that finds a confused and terrified baby goat accidentally separated from the rest of the flock and struggling to find its way home.

If the film merely resolved this passage, it would qualify as a satisfying and unusually noble effort. Frammartino has more ambitious concerns on his mind, though. He wants to raise the material to a spiritual level -- to link the old man, the goats, the dog, and the geological process of the prologue in a kind of allegorical meditation on the circle of birth, life, and death, which is why the material ends cyclically with the same image as its opening scene. Although this transition is intellectually commendable, it doesn't deliver on an emotional level. The film merely abandons the baby goat in the forest, and we don't feel eager for some transcendent metaphysical truth; we want to know, very specifically, what happened to the animal, and feel betrayed when the movie doesn't tell us. One can admire Frammartino for attempting to connect the specific and concrete with the lofty and philosophical, but if there is a way to achieve this goal within the context of the events depicted onscreen, he doesn't find it.