When film professors and Ph.D. students engage in dry discourse about film adaptations, they often choose to ignore the most basic and most substantial aspect of having multiple versions of a text. A film based on a book provides (re)viewers with a built-in "anchor," or point of comparison, which will inherently dictate the flow of discussion like an analytic magnet. The strengths of "high" literature, which are notoriously unreproducible in cinema, thus become weaknesses of the film, often before the lights of the theater have even dimmed. With this in mind, director/producer Steve Jacobs and writer/producer Anna Maria Monticelli deserve applause for even attempting to adapt J.M. Coetzee's novel Disgrace for the screen, and their ambition makes the project a success, even if the final product is discernibly flawed.

Few novels of the latter half of the 20th century garnered more critical praise than 1999's Disgrace, which brought Coetzee an unprecedented second Booker Prize and propelled him to the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2003. The novel, which charts the fall of a white South African professor after his forced affair with a mixed-race female student becomes public, has a strong narrative drive, but, like all great literature, Disgrace is primarily a meditation on the inability of language to express what is most essential about our existence and a celebration of the author's determination to keep writing anyway. That same spirit is captured by this moving film, as Jacobs and Monticelli subtly and successfully heighten the tension built by the plot by examining the frayed relations within a society where surface disparities easily overwhelm more fundamental similarities. Questions of race, class, family, and religion are so indelibly interrelated that the characters inevitably find the hierarchy of their loyalties to these social markers becoming condensed and constricted, until they fluctuate under observation, like the particles of quantum physics.

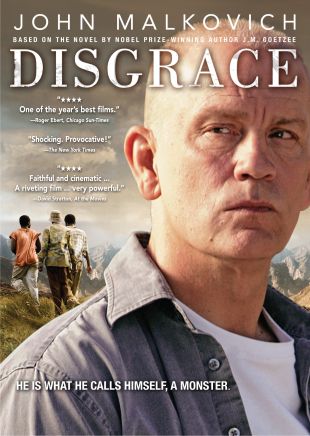

John Malkovich provides his usual standout performance as David Lurie, a professor of Romantic literature, who self-justifies his immoral actions with antiquated notions of the righteous nature of individual passion and desire, gleaned from the poetry of Lord Byron. On the surface, Lurie's philosophy is brightly tinted with hints of benevolence, in that it makes every experience into an opportunity to learn to live better, but the darkness beneath the optimistic glitter is soon exposed when he and his daughter are viciously attacked, thus becoming the objects of another's violent desire. As the characters begin to react in surprising ways to this seminal event, the audience senses the gaps where, in the book, Coetzee's superlative introspective prose adeptly nurses the reader through the complexities of their shifting moralities. While it would be indefensible to advise that someone see this movie in lieu of reading the novel, anyone who has either already read the book or has no plans to read it has much to gain from this compelling film.