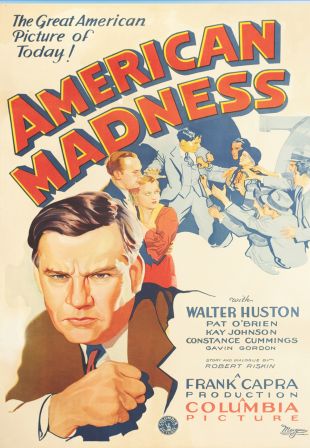

American Madness was the first of Frank Capra's topical social dramas, anticipating his later, broader work in this sub-genre with Mr. Deeds Goes To Town, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, Meet John Doe, and It's A Wonderful Life (two vital elements of which -- a key scene midway through the picture and the denouement -- were derived from the key dramatic moment in this movie). Indeed, it stands at the nexus of Capra's early career, between actual events that took place at the Bank of Italy, involving its founder A. P. Giannini, and the decade-and-a-half of cinematic storytelling that the director would generate out of moments such as that. And for fans of the filmmaker's uplifting, socially conscious brand of story-telling (which also figures into such comedies as It Happened One Night and You Can't Take It With You), this film is a great discovery on that basis alone. Some may chide the script for some improbabilities, such as the idea that bank president Thomas Dickson would hire a felon and housebreaker as his head cashier; or that seemingly to a man, the people that Dickson has helped out with his liberal loan policies would be willing and able to mount a rescue effort of the bank. But those flaws can be overlooked in the context of the bigger picture here -- in 1932, Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin were getting away with a lot just making a movie like this, which was not entirely well-received in cities that had seen bank runs in recent months and years (it closed in Baltimore, where such incidents had occurred, in just two days). But American Madness is much more than a social statement -- it's a great visual and cinematic narrative achievement, showing how a master filmmaker's vision, coupled with that of a bold screenwriter (Robert Riskin, who would loom large across Capra's career through the 1940's), could devise what amounts to a symphony on the screen.

Watching American Madness today, one is struck by how Capra uses the bank building itself, a huge edifice with a towering, vault-like ceiling (resembling at least one bank that is still standing at this writing in 2009, and being used as a bank, the Apple Bank for Savings at Broadway and 73rd Street in Manhattan) -- the building is not only the framework for about 95% of what we see, but is virtually a character in the drama, as much as Walter Huston's Thomas Dickson or Pat O'Brien's Matt Brown; indeed, for the first 10 or 15 minutes, Capra seems to be giving us a "Grand Hotel"-style sweep of the players, with the bank as the "star"; except that American Madness was released about six months before MGM's Grand Hotel. And the interwoven stories are a little too closely related to two parallel events -- Dickson's battle with his board of directors and head cashier Cyril Cluett's perfidy -- to quite match that more celebrated movie's broad, vast canvas of events. But the scope of the vision is there, and amid the sweeping, occasionally breathtaking camera angles (all made possible by that building's vastness -- so that we sometimes seem to be seeing events from the bank's point-of-view), and the bracing forward momentum of the narrative, plus the energetic performances of all concerned, the result is a fine, moving drama as well as a visual delight.

Had it been done in the silent era, American Madness might have found more acceptance, though it wouldn't seem quite as striking today -- but in 1932, filmmakers were still figuring out what could be done with sound as a narrative device, and the opportunities that it opened up, in terms of devising scenes and editing them; there's no music anywhere in American Madness -- as it pre-dates the point where filmmakers could see the use of a score as a dramatic device in talkies -- yet the careful use of sound and fine pacing of the performances keep things moving at a brisk pace. Edward Bernds, who was already a top soundman, deserves some credit for the technical success of the movie, as does cinematographer Joseph Walker, whose lighting is gorgeous when he's shooting those bank interiors. But the real triumph here belongs to Capra and Riskin, a conservative Republican and a liberal Democrat, respectively, who found a common ground and common purpose in devising this tribute to the common man. (Note: Just to demonstrate the potency of Riskin's screenplay, the central part of his story is echoed, to an extent, in Arthur Hailey's book The Moneychangers and, even more so -- in terms of the way it is presented -- in Boris Sagal's 1976 miniseries of the same name, written by Dean Reisner and Stanford Whitmore, though it must be conceded that Riskin, Hailey, Reisner, and Whitmore all had as their inspiration the same source, Giannini and Bank of Italy-nee-Bank of America).