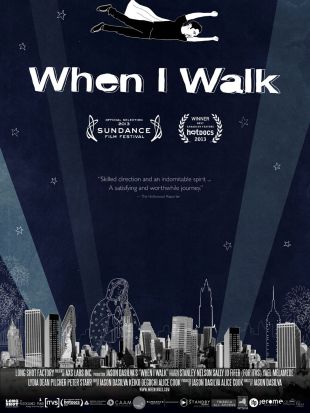

The past couple of decades have witnessed a surge in personal-essay films, coincident with -- and made possible by -- the increased accessibility and falling cost of digital video. These projects carry with them an array of potential casualties: They can often wax boring, self-indulgent, narcissistic, too "inside," or any combination thereof. Couple those considerations with the de facto risks of making a disability-themed chronicle, and the odds of nailing a two-in-one -- a successful self-reflexive documentary about a physical impairment -- are slim to nonexistent. For that reason, husband and wife Jason DaSilva and Alice Cook's movie When I Walk both serves as a testament to the genius of its creators and strikes one as a small cinematic miracle.

DaSilva had already established himself as a financially and critically successful documentarian in the early-to-mid '00s, with projects funded by and airing on PBS, HBO, and the CBC. Then, in 2006, personal disaster struck: a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis -- one of the most physically crippling of all disabilities, causing diminished locomotion, eyesight, hearing, speech, and a host of other rudimentary skills. It was particularly devastating for DaSilva, given his commitment to an art form that necessitates mobility and an oeuvre woven around the themes of multiculturalism and global travel. He began to ask himself if it would even be possible to continue as a director. Never one to slink away from a difficult task, DaSilva then began shooting a documentary on his journey with MS. Along the way, he fell in love with Cook, married her, and fathered a child -- and by the midpoint of shooting, Alice became an integral part of the creative process and a subject in the film.

The resultant movie is remarkable for a whole host of reasons, but the most basic is its uncanny ability to blend two elements that sound incompatible: an unflinching look at DaSilva's motor impairments with his adamant refusal to beg for sympathy. We witness footage of DaSilva struggling to stand up at the beach, his legs bowing and buckling beneath him, and attempting to walk normally, with one foot dragging so severely that he consistently risks tripping. These scenes carry with them a palpable horror -- we can imagine the sudden loss of the capacity to stand or walk, and we feel his helplessness and inner onslaught of terror. We can also infer the breadth of courage that it required to interpolate such shots into the film; DaSilva is placing his physical vulnerabilities and weaknesses on center stage before millions of viewers, when every director who includes him or herself within the frame strives for the opposite -- to seem noble and graceful. But even more interesting is the way that DaSilva gamely resists pity: He's lightly self-deprecating in a way that takes the edge off of the sadness -- smiling at the irony of his situation and inviting us to join him. He also finds a magnificent comic foil in his middle-aged Indian-American mother, a no-nonsense cynic whose refusal to sugarcoat anything provides many of the documentary's biggest laughs, and who walks away with every sequence in which she appears. Because the movie's drollness gives us a bit of distance from the footage, and because the director never attempts to forcibly extract emotions from us, the irony is that we find ourselves caring ten times more -- and those sentiments grow even deeper in the later stages of the film, as a very pregnant Alice begins turning the camera on herself and confessing her most intimate hopes, fears, and concerns about the future, her every word comporting deep resonance. At one point, DaSilva -- in desperation -- visits Lourdes in the hope of receiving physical healing from Mary; sans any improvement, one of the participants in the film reminds him that he did, in fact, experience a miracle: when Alice entered his life. We can believe it; these two were born to be together.

The other unexpected element that raises this documentary to a higher plane is DaSilva's sense of style. A strong aesthetic signature is not something that one often associates with documentaries, least of all this type of introspective essay picture. But DaSilva keeps adding little masterstroke flourishes that single out this movie. An illustrator for many years, he cuts beautiful black-and-white sketches -- stylistically reminiscent of Marjane Satrapi -- that occasionally spring to animated life. And he also periodically returns to a sobering visual motif: time-lapse cinematography of passersby zipping up and down the street, while he is seated in the middle at a total standstill. This wasn't merely an aesthetic whim, of course: It functions as a clever metaphor for the day-to-day experiences of the MS sufferer.

All of this, by itself, would make the documentary a triumph, but it has yet another hidden ace up its sleeve before the end credits roll: Just when we think that the film couldn't possibly improve, DaSilva and Cook introduce a social-activist element. During the course of their journey, they discover an appalling travesty: Manhattan lacks taxicabs for the physically disabled, and a shocking number of NYC-area restaurants are not wheelchair-accessible. Thus, the documentary concludes with the two protagonists' crusade to try to increase the number of public accommodations for the handicapped. They begin a massive project called AXS Map, which involves systematically documenting every place of business that falls into this category; it is eventually made available as an iPhone and Android app, and covers much of North America.

The directors have therefore set a unique and ambitious social agenda for the motion picture that extends far above and beyond what is actually onscreen: using the documentary to build increased awareness of multiple sclerosis, as well as catalyze broader and more systematic attempts to reach out to the disabled, within the community at large. Only time will tell if the movie has this long-term impact. However, its abundance of empathy and compassion provide the best possible starting point that one can imagine.