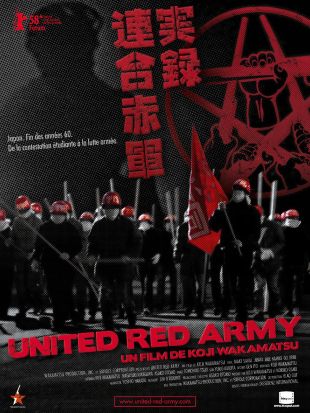

Director Koji Wakamatsu's historical epic United Red Army attempts to dramatize the lengthy, byzantine history of the titular cadre, an SLA-like militant terrorist group that formed in Japan in the late '60s (as an offshoot of its country's student protest movement) and attacked various sectors of Japanese society. The subject is intriguing, and one can admire Wakamatsu for attempting to tackle it, but the film feels amateurish and only fitfully satisfying.

The docudrama opens with an expository sequence that brings the audience up to speed on various historical developments that contributed to the formation of the Red Army -- a 15-20 minute prologue, synthesizing grainy documentary footage, and staged dramatic scenes. That stylistic amalgam may sound promising, but it falls to pieces given the lack of clarity of the archival material. The clips are so visually murky that we end up relying exclusively on the explanations of the narrator and the onscreen titles that spell out what is happening, draining the material of all dramatic tension. Wakamatsu also gives us an excess of detail -- so much so that we begin to lose track and grow hopelessly confused. This applies less to the nuances of the history that flash before our eyes than to an excessive number of character identifications. In more effective historical dramas, we get a reasonably small number of central characters and then follow their individual and collective experiences over a set period of time. Here, there is no such focus: dozens and dozens of characters turn up, and Wakamatsu identifies each one with an onscreen title -- and he keeps doing so even up to the film's two-hour mark. This extends to peripheral, inconsequential figures -- those who only appear for a minute or two before being shot dead, strangled, or arrested. At one point, Wakamatsu even tags a couple's infant son with a name, though the baby has no discernible role in the drama.

As a result of this, we become hopelessly bewildered trying to keep tabs on who is who; the onscreen figures meld into an inseparable, clamoring mob in our minds. And because there are so few characters whom we can identify apart from the pack, the movie gives us an inadequate number of emotional handles to hang onto; there are flecks of humanity and fleeting moments of drama, but Wakamatsu seldom sticks with any one arc long enough for us to watch a particular character evolve over time, and truly share his or her feelings. If this represents a glaring miscalculation for the first 30 or 40 minutes, it grows deadly during the film's next hour -- an endless, excruciating series of torture sessions perpetuated by the Red Army and set in a rural cabin. Wakamatsu films these events in such dim light that it's often difficult to determine the identities of the various victims, or what their individual motivations are. Instead, we get endless screaming (most of it from the army's deranged ringleader, Mori), brutal physical abuse, executions of dissidents, and repetitive references to the army's philosophy of "self-critique" -- a technique that forces each pariah to publicly reflect on his or her behavioral "mistakes," acknowledge areas of weakness, and oratorically proclaim a different path for the future.

Fortunately, the second half of the film rebounds somewhat and piques renewed interest from the audience, as the terrorists flee through the wilderness and mount a final standoff against authorities at a mountain lodge. These sequences also grow tedious, though, and lose whatever excitement or tension they initially generated because they take up far too much screen time. Overall, one can't help but feel that Wakamatsu colossally misjudged how to parse out events in his narrative. Had he been more selective with expository details and character development at the outset, and dramatically cut back on the amount of time spent on torture sessions and the cabin standoff, he could have balanced the film more while retaining a sweeping, epic feel. It also might have worked much better as a series, thereby giving Wakamatsu the freedom to develop individual characters in longform, over the course of many episodes.

Admittedly, some elements of the film do succeed. For example, one brief torture sequence stands out from the rest -- as a beautiful young Japanese woman gets sucked into the political cult, and Mori forces her to beat herself (first to the point of deformity, and then to death) in front of spectators. As she dies, Wakamatsu cuts to various events from her life, and we instantly grasp the discrepancy between the noble political ideals that set her on the path to the Red Army and the psychotic brutality that now surrounds her. Remnants of this theme crop up several times throughout the movie and serve as an appropriate (and reasonably profound) foundation. Also, despite the opaqueness (and interminability) of the torture and standoff sequences, Wakamatsu does achieve some distinction by refusing to depict events outside of the inner cult; for example, we see the militants firing weaponry from inside of the cabin, and hear the opposition clustering around the perimeter, but the camera never leaves that inner space. This gives us the appropriate sense of claustrophobia and paranoia that the army must certainly have felt during its final hours.

These strengths, however, are the exception rather than the rule. As indicated, the subject of the United Red Army could easily provide endless opportunities for compelling onscreen drama, but most of them go untapped here.