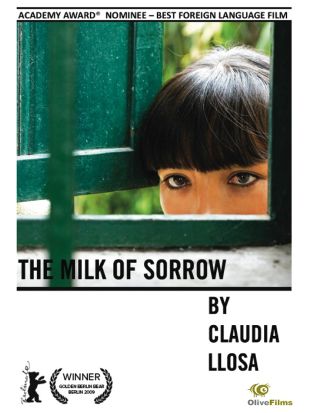

A haunting, ascetically delicate lead performance lies at the heart of Peruvian director Claudia Llosa's feature The Milk of Sorrow that just about rescues the drama from its central failings. The movie opens with a couple of unusual sequences that summarize the movie's core themes. An ailing, middle-aged Peruvian woman named Perpetua (Bárbara Lazón) utters a sing-song chant, bemoaning her own brutal sexual torture years ago at the hands of local terrorists -- and her twentysomething daughter, Fausta (Magaly Solier), responds in almost perfect psychic harmony by extending the mother's lament into a contrapuntal melody of reassurance. After the old woman dies, and Fausta gets hospitalized following a hemorrhage, we discover a bizarre and rather grotesque fact about the young girl: terrified of the prospect of her own rape, Fausta has placed a potato inside her vagina, reasoning that any sexual deviates who dare to assault her would not only feel instant revulsion at the presence of the foreign object, but implicitly find it difficult to withdraw the tuber. The problem with this twisted pseudo-panacea, of course, is a practical one -- the potato also threatens to cause severe vaginal and uterine infection.

Llosa uses the self-violation undertaken by Fausta as an indication of the young woman's inheritance of scars from her mother; Fausta's uncle refers to the plague as the "milk of sorrow," a kind of local hereditary "curse" passed down through maternal breast lactate. But one can also logically justify Fausta's trauma by deducing that the mentally battered matriarch abused her impressionable young daughter with inappropriate tales of her own victimization such as the one we hear in the deathbed sequence. The mother thus set the girl up for years of sexual phobia.

The film largely succeeds in the area of Solier's shattering dramatic evocation. The actress' lack of conventional beauty works to her full advantage: the 24-year-old thespian couples a striking seductiveness with the austere, heavily worn facial features shared by thousands of other Peruvian women, so that one can read, in her weathered countenance and bloodshot eyes, the legacy of misogynistic horrors wrought by generations of sadistic military operatives. Moreover, Solier packs so many multifaceted, conflicting emotions into each shot that she never sinks below the level of thoroughly magnetic.

The film incorporates another strength as well -- an unusual one. In lieu of confining the narrative to Fausta's story, Llosa cuts back and forth between this tale and broader, vaguely satirical views of contemporary Peruvian life that paint it as carnivalesque, sleazy, and garish -- which manifest particularly strongly in a wedding celebration for Fausta's female cousin. The writer-director uses the juxtaposition of Fausta's story and the broader events to create an ironic contrast between the tackiness that the filmmaker perceives to be cloaking contemporary Peruvian society and the rather sobering horrors that still exist on the level of individual Peruvian citizens. Nowhere is this more telling than in a startling sequence that has an obnoxious portrait photographer shooting pictures of the wedding party; they abandon the garish, painted tropical backdrop used for the shoot, and Fausta remains after the group departs -- crushed, forlorn, and isolated, her emotional horrors made all the more real when preceded by the photographer's insipid joviality.

Unfortunately, though, the movie is flawed. Despite the richness and comprehension of the character that Solier brings to the screen, the audience compassion toward Fausta that she manages to generate (much of it, admirably enough, from long, wordless sequences), and the fascinating thematic threads of Fausta's personal demons and Llosa's criticism of Peruvian society, the ultimate power of the movie diminishes given the writer-director's excessive reliance on the metaphoric. In lieu of mapping out Fausta's torturous journey back toward psychosexual health within a realist framework (as she searches for a way to give her mother a respectable burial), the writer-director immerses the movie in obscure magic realist symbolism. Consider, for example, a song that Fausta improvises, late into the movie, about mermaids picking quinine. Or a bizarre sequence that witnesses a kindly gardener passing Fausta some candy, at which point she furiously thrusts it down onto the soil, and the single leg from some blue jeans that makes a sudden appearance beneath Fausta's skirt. Or a final shot where Fausta leans over a flower pot and sniffs a daisy -- apparently intended to re-evoke an equally indecipherable floral metaphor from earlier in the picture.

One doesn't doubt that each of these symbols claims multi-layered significance within Peruvian culture, but their meanings will be lost to the vast majority of international viewers. More problematically, the narrative itself loses coherency as it lurches toward its conclusion. It's infuriating, in a way. Llosa begins with a very tangible, emotionally complex, and socially relevant situation, anchored by an incredible performance and some intriguing themes, and then refuses to resolve or even work through the material in a comprehensible manner.