The image of young Benjamin Braddock appearing at his parents' swank pool party fully clad in scuba gear remains one of the most satisfying images of youthful alienation ever captured on celluloid. Confused, cut off, and trapped in the claustrophobia of trying to figure out what he's going to do with himself, Benjamin is a model of dissatisfied aimlessness caught up in the whirl of parental and societal expectation. Not surprisingly, his character struck a chord with 1967 audiences, and The Graduate became the highest-grossing film of 1968 and a landmark in the cinema of hip, New Wave, antiestablishment disillusionment. While an enduring classic for its perpetual topicality, and a harbinger of similar dissections of youthful disenchantment that permeated the late '60s and 1970s, The Graduate was also remarkable for providing an unrevolutionary revolution. Benjamin is ultimately a bored, confused young man who has an affair with an older woman (played by an actress only six years Dustin Hoffman's senior), discovers he loves her daughter, and impetuously absconds with the girl to a future offering yet more disillusionment. To top it off, Benjamin's not even that great a guy, more of a conflicted muddle than a viable counter-culture hero. He doesn't want to end up like his parents, but he happily drives around in the Alfa Romeo they give him as a graduation present. He even ends up running off with the very girl they picked for him in the first place. But while it's easy for contemporary viewers to regard the film's message as compromised, The Graduate was something new and provocative for late '60s audiences, a slyly wrapped package of antiestablishment sentiment. Benjamin Braddock's very imperfections made him a believable vehicle for youthful malaise in the first place; to a generation disillusioned with the prosperity in which they had been raised by indulgent parents, Benjamin's brand of resentful ennui resonated on a visceral level. In painting a portrait of an imperfect youth rejecting an equally imperfect world, Mike Nichols and Buck Henry offered only satirical possibilities instead of self-affirming answers. Instead of driving off into the sunset in his Alfa, Benjamin and his beloved board a dirty city bus, hesitant to look either at each other or at the future they have chosen.

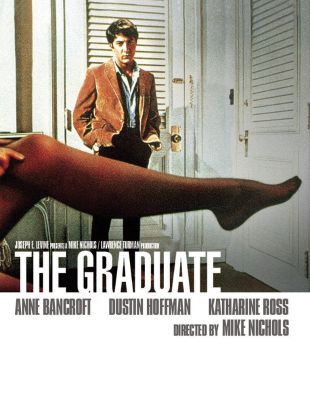

The Graduate (1967)

Directed by Mike Nichols

Genres - Romance, Drama, Comedy |

Sub-Genres - Coming-of-Age, Sex Comedy, Comedy of Manners |

Release Date - Dec 20, 1967 (USA - Unknown), Dec 21, 1967 (USA), May 1, 2013 (USA - Rerelease) |

Run Time - 105 min. |

Countries - United States |

MPAA Rating - PG

Share on