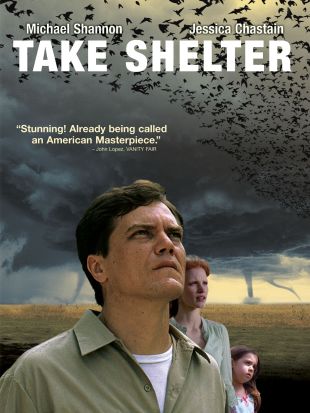

Mental illness can be an incredibly difficult subject matter to portray in film; even if the screenplay is written with sincerity and a genuine sense of authenticity, a poor performance or misguided directorial choices can easily taint the whole endeavor. In Take Shelter, writer/director Jeff Nichols presents a sensitive and extraordinarily expressive profile of a hardworking family man contending with the slow onset of schizophrenia. With the talented Michael Shannon in the lead and a screenplay that allows the audience inside his character's head as his mental deterioration progresses, the viewer can't help but get emotionally involved.

/_derived_jpg_q90_584x800_m0/22055592_PA_Take-Shelter.jpg)

Curtis LaForche (Michael Shannon) has a good life. He lives in a beautiful house with his loving wife, Samantha (Jessica Chastain), and their deaf six-year-old daughter, Hannah (Tova Stewart), but he begins to sense that something ominous is on the horizon when the dark clouds of swelling storms begin invading his dreams. The taciturn Curtis refuses to discuss the dreams with anyone, but he feels compelled to dig out a massive storm shelter with the help of his good friend Dewart (Shea Whigham). Meanwhile, as Samantha grows increasingly concerned with Curtis' erratic behavior, the local rumor mill begins to churn. Are Curtis' dreams an omen of things to come, or is he perhaps headed down the same dark road as his mother, who was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia when she was approximately the same age that he is now?

With a filmography that reads like the inmate list at a small psych ward, Take Shelter star Shannon has excelled at portraying deeply disturbed characters in movies such as Bug and Revolutionary Road. Here, Shannon infuses Curtis LaForche's increasing instability with a sense of desperation that makes it impossible for the viewer not to sympathize as he becomes a pariah at his job, in his community, and -- most painfully of all -- in his own home. Curtis is a man whose body exists in the real world, while his mind is being sucked helplessly into a darker mirror image of reality where his loved ones have turned malevolent and Mother Nature has decided to strike back against mankind. Shannon's quietly intense performance conveys the anguish of such an agonizing experience in a way that never feels exploitive or overplayed. He's simply a man who seeks to protect his family, but can't realize that he may be the biggest threat of all. A powerful scene in which Curtis nervously visits his schizophrenic mother in an assisted-care facility not only says quite a bit about the protagonist's character -- he remains dutifully composed while his fate becomes frighteningly clear -- but also about writer Nichols' talent as a screenwriter who recognizes the power of minimalism.

Meanwhile, as a director, Nichols creates such an intense aura of dread and impending apocalypse during the visions that when Curtis simply describes one that is not shown in the film, we shudder at the mental image it paints. Curtis' wife Samantha is without question the character in the film who bears the most of his mental breakdown, and actress Jessica Chastain beautifully conveys the conflicting fear, anger, and concern that goes along with watching her husband's painful deterioration. Likewise, rising actor Whigham continues his winning streak of colorful supporting characters; in films such as Machete and Barry Munday, Whigham has displayed a penchant for the cartoonish, but by toning it down in Take Shelter, the talented supporting player displays a flair for drama that has been conspicuously absent from many of his higher profile roles.

Despite the surreal flourishes on display during Curtis' dreams and hallucinations, Take Shelter unfolds in a straightforward manner that is only betrayed in the film's final scene -- a tantalizingly abstract coda that seems to be more figurative than literal. And while some may question Nichols' decision to abruptly depart from his realistic approach so late in the game, the ending is intriguing more for what it doesn't show, rather than for what it does.