/_derived_jpg_q90_584x800_m0/Paris2008-Still1.jpg)

Some movies declare their sources openly. Director Cédric Klapisch's seriocomedy Paris falls squarely into this category, aspiring to establish itself as the definitive French version of Robert Altman's Short Cuts. The similarities are innumerable: multiple crisscrossed substories in an urban landscape that each receive a scant amount of screen time; quirky existential reflections on fate, chance, and the degree to which a broad patchwork of intersecting lives can yield a ripple effect and impact individuals in startling ways; a central despair and sadness about the pitfalls of the human race, offset by flashes of dark humor.

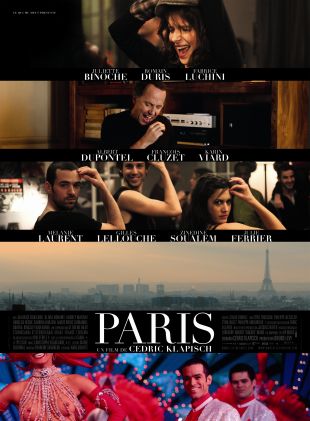

The film is comprised of several mini-narratives. The main strand tells of nightclub dancer Pierre (Romain Duris) and his social worker sister, Élise (Juliette Binoche), mutually stricken by the discovery that Pierre suffers from a debilitating heart condition and will soon require a coronary transplant with a 40-percent chance of survival. In another substory, the dumpy, middle-aged professor-turned-television host Roland (Fabrice Luchini) buckles beneath the weight of infatuation for a sexy twentysomething student (Mélanie Laurent) and begins anonymously sending the baffled woman erotic text messages. And in still another (set outside of France), a Cameroonian man named Benoît (Kingsley Kum Abang) grows so desperate to relocate from Africa to Paris that he's willing to risk life and limb via a dangerous ocean passage to French shores. More tales, or fragments of tales, also crop up, but are too numerous to mention.

/_derived_jpg_q90_584x800_m0/Paris2008-Still3.jpg)

Klapisch's willingness to wear his influences on his sleeve isn't necessarily a detriment, aside from a couple of nods to Louis Malle's The Fire Within that only make this film look inferior in comparison. In recent years, directors have used the narrative model of intersecting characters to varying degrees of success, but the overall concept works admirably here, as do Klapisch's open-eyed ruminations on the bittersweet qualities of human life. He's an unabashed romantic at heart, as evidenced by the wonderful scenes in which characters pair off in unexpected couplings, but he also has a supple hand for lighthearted and daft humor; in the film's best moments, the sexiness and joviality work hand in hand to create a magical aura that blankets the onscreen atmosphere. In particular, the sequences involving Roland's text messages score a bull's-eye. We laud his gutsy, almost foolhardy lyrical effusiveness with a virtual stranger, and yet the texts (read by Luchini in voice-over) grow just absurd enough -- with over-the-top, imposing sexual imagery more at home in a Harold Robbins novel -- that they earn their fair share of genuine laughs. Binoche also has a wonderful scene that demonstrates the same tonal balance of eroticism and humor, in which she does an alluring striptease for a lover (Albert Dupontel) while giggling continually -- a scene that concludes with Dupontel practically buried beneath the clothes she's thrown onto the bed.

/_derived_jpg_q90_584x800_m0/Paris2008-Still5.jpg)

Paris also benefits from heart-rending interpersonal relationships among its characters. Klapisch has a knack for establishing the emotional texture of specific human connections, with all of the little contradictions and reversals intact, and maintaining credibility throughout -- undergirded by a series of top-shelf performances from French vets.

/_derived_jpg_q90_584x800_m0/Paris2008-Still7.jpg)

For all of its strengths, however, the film suffers from two setbacks. First, whereas Altman and some of his protégés, such as Alan Rudolph and Paul Thomas Anderson, have understood the importance of narrative balance, Klapisch doesn't. He pays an inordinate amount of attention to the Pierre-Élise and Roland tales, and they retain interest, but detract from the screen time afforded to additional substories. The tale of Benoît may well be the most fascinating element of the movie -- culminating with a magnificent, almost mythical shot (the picture's best) of a moonlit ocean tossing around a frighteningly small boat, crammed to the gills with Africans -- but we never learn much about that story. Other narrative additions, which receive even less screen time (including one tale that only builds in the third act), feel like superfluous afterthoughts at most. Klapisch also falls prey to stylistic self-indulgence on a handful of occasions, as when he interpolates a *Sims-like CG-animated sequence as part of one character's nightmare, or when Roland gazes at hand-held movie footage of himself as a young dancer and Klapisch brings those images to life in a pop-art vein, with an exotic dance sequence framed by the exterior edges of the celluloid.

Nonetheless, Paris is absolutely worth seeing; while it fails to make any grandiose or earth-shaking statement, many of the individual sequences, insights into human behavior, and performances achieve something close to perfection. But the film as a whole adds up to less than the sum of its many wonderful components. One only wishes that Klapisch had toned down his excesses and paid more attention to the intriguing narrative details that are given short shrift and leave the audience somewhat unfulfilled.