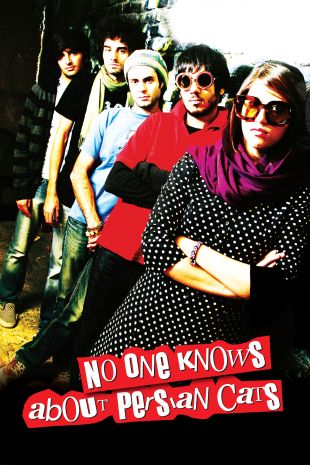

A fascinating story lurks at the heart of Iranian director Bahman Ghobadi's contemporary comedy drama No One Knows About Persian Cats, and if films existed only on a literary plane -- if they could be evaluated solely based on the strength of their stories and dialogue -- it might qualify as a satisfying effort. But, unfortunately, the film represents a miscalculation from the gifted creator of A Time for Drunken Horses and Turtles Can Fly.

This is the tale of Nader (Hamed Behdad) and Ashkan (Ashkan Koshanejad), two young citizens of Tehran who get released from prison and embark on a music career, but mutually chafe under the oppressive weight of limited Iranian artistic expression and brutal government oppression. The friends harbor a shared dream of a farewell Iranian show, followed by a string of concerts across Europe, but a number of key obstacles stand in the way of their expatriation -- not least of which is the need to purchase passports and visas from a questionable black-market dealer at almost prohibitively expensive prices. This is a country, Ghobadi reminds us, so dictatorial that it refuses to let its citizens even wear ties in passport photos, and so invasive that cops regularly pull over drivers to seize (and put to sleep) their sweet little puppy dogs -- actions apparently borne out of sanitary concern. It shouldn't come as a surprise that an "underground" music culture would flourish and thrive in this anti-cultural prison, and part of the movie's fascination in its early stages blossoms from its ability to pull us into that realm with great ease.

For a time, the film indeed coasts along on the strength of its unusual premise and Ghobadi's funky deadpan humor. He has quirky instincts, and many of the individual details (such as a supporting character who names his pet bird Monica Bellucci, or a metal band who play in a barn and upset the cows with their music) elicit their fair share of genuine laughs, while the central narrative conceit carries a sad poignancy; we begin to grow emotionally invested in Ashkan and Nader and hope for positive outcomes in their lives.

Nevertheless, this emotional investment is temporary. Ghobadi's curious style starts to work against the material as the film progresses. He establishes the reality of his central characters in two aesthetic extremes: cinematographer Turaj Aslani shoots the day-to-day of Nader, Ashkan, and those they encounter in a kind of flat, unforgiving realism, frequently saturated with muddy browns and shot in low-level light, at enough of a distance that it's often excruciatingly difficult to determine the identity of every character onscreen, and their relationships to one another. For the music sequences, on the other hand, the director utilizes a kind of hyper-charged post-MTV aesthetic that cuts away from the band to a series of montages and presents us with a blizzard of images taken from urban Iranian life.

On a conceptual level, this very deliberate approach sounds like it could be stunning -- contrasting the dull reality of oppressed Iranians with the razzmatazz generated by Western music -- but it has the odd effect of undercutting the cohesiveness of the material. As if it weren't difficult enough to distinguish between the major characters and avoid confusing them (especially given the strong resemblance between two of the male leads), the montages carry us even further away from the two central characters and their various acquaintances. Aside from one inspired sequence when Ghobadi ingeniously overlays the wailing song of an Iranian musician over images of dire poverty, many of the sights glimpsed in the cutaways seem random and haphazardly chosen. But the most fundamental problem with this approach is a very straightforward one: the montages themselves lack the beauty and joy that one associates with real social and cultural liberation. They feel forced, heavy, imposing -- even full of dread. Ghobadi's ideas and observations throughout the film are certainly valid, but his visuals work against the material by muddling up the clarity of its basic exposition and aesthetically suggesting that he lacks the conviction necessary to give the central themes lift.