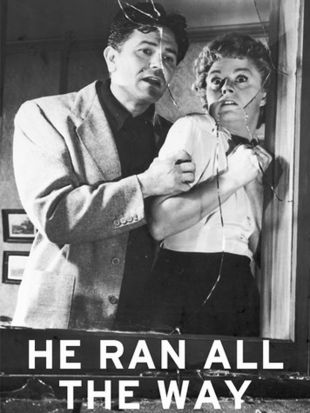

John Garfield's final film was completed and released (through United Artists) the year before his death at age 39. It is of a piece with Body and Soul (1947) and Force of Evil (1948), produced -- as were those others -- by Bob Roberts, and directed by John Berry, who was a future blacklistee, as were the directors of the two earlier movies, Robert Rossen and Abraham Polonsky. And as with those earlier films, He Ran All the Way embraces lots of dark social and psychological themes in the course of telling what, on its surface, seems to be an action-oriented story.

Garfield is excellent in a difficult role, playing a dangerous (and mostly unpleasant) character in Nick Robey, and walking a fine line all the way through between evoking revulsion and fear -- over what he has done and what he always seems poised to do next -- and vulnerability and momentary flashes of sympathy. Robey's only slightly redeeming qualities may be the combination of his very slightly "soft" edge, which puts him just a step or two away from starting out as a habitual murderer, and his slightly (but definitely) limited intelligence, which combine to make it difficult for him to form the sustained, conscious intent -- in the intellectual sense -- to kill someone; his obvious past victimization by an alcoholic mother (Gladys George); and the moments of unintended articulation that come out of his mouth, as when he is able to say, in an aside when he is threatening to kill a hostage, that a stray cat would have been treated better than he is. He might not be the brightest man in the world, but he's not blind, and he is sensitive in his own peculiarly vicious way. Of course, this observation and the motivations behind it only point up the sociopathic nature behind Nick's persona -- he is oblivious to the fact that he was the one who felt threatened by something perfectly innocent, and panicked, and pulled his gun and started this nightmare. Garfield's success is in convincingly evoking a character driven by paired feelings of deprivation and entitlement -- an extremely dangerous combination in a man carrying a gun -- and, yet, imparting just enough sympathy and humanity to Nick that one can accept (or, at least, not scoff at) the idea that a shy, lonely girl like Peg might actually be ready to run off with him, if it would also help to save her family. This was one of the two or three most difficult roles of Garfield's career, as he plays the ultimate outsider, a completely alienated sociopath; peculiarly enough, the most sadistic moment in the movie comes not in the shootings, but an scene involving a sewing machine and an accident caused by his character's incessant tormenting of Mrs. Dobbs (Selena Royle). This is a moment when Nick cracks and, for an instant, feels genuine remorse, and Garfield is totally convincing in the scene.

Shelley Winters also shows more depth, range, and intensity than most filmgoers thought possible at this early stage of her career -- she matches Garfield perfectly, and the rest of the cast (especially Royle and Wallace Ford) also rises to the occasion. James Wong Howe's cinematography is first-rate, filled with gorgeous, threatening shadows, odd angles, and compelling close-ups, and Franz Waxman's score is surprisingly inventive, even working in moments of lightness, as in one night-time scene involving Nick and a boy hostage that is scored to solo clarinet. And as with Body and Soul and Force of Evil, the movie is filled with blacklistees, including one-time Broadway star Selena Royle, character actor Norman Lloyd, and producer Roberts, and director Berry, who subsequently moved to France.