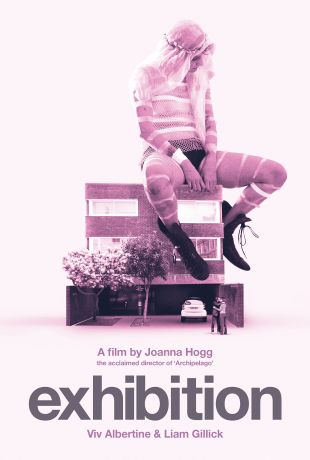

English director Joanna Hogg's Exhibition seems aptly titled. It's a curio, a sophisticated museum piece, with a conspicuous absence of dramatic momentum. But that is exactly Hogg's point; the psychically damaged married couple who take center stage here are voluntarily caught up in self-defeating Sisyphean cycles that have turned their lives into an infernal hell. A sense of suffocating inertia dominates the onscreen environment. This feels suitably anhedonic, but the main characters are also so meaty and rife with contradictions that one feels grateful for Hogg's willingness to afford her audience two hours of protracted observation and study in lieu of tossing the subjects into some faux narrative contrivance.

Viv Albertine and Liam Gillick star as, respectively, D. and H., a childless couple cohabitating in contemporary London. She's an illustrator, he's a builder. Their residence is something else. Designed in real life by the late GMW architect James Melvin, the structure is reconceived within the context of the movie as H.'s creation -- with such ghastly connotations that the end-credits dedication to Melvin seems less like an homage than a very mean rib. More specifically: Hogg uses Melvin's trademark curtain walling and steel-cantilever supports -- publicly and historically regarded as arbiters of modernist elegance -- to instead function as some sort of diabolical glass penitentiary in which the couple have ensconced themselves. For much of the picture, we get the constant dissonance and cacophony of life beyond the frame populating the soundtrack -- sirens wailing, cars crashing, bulldozers shredding concrete -- and Hogg constantly implies that the husband and wife have drummed up a sociopathic way to shield themselves from external madness.

There are also arcane references in the couple's exchanges to some past horror that befell them, which Hogg deliberately refuses to articulate. In one pivotal scene, H. puts on all-black evening clothes and prepares to venture out into the world, but D. has an anxiety attack, imploring him not to leave the flat lest "the same thing happen again." Some might find Hogg's opacity regarding the backstory willfully perverse, but her ambiguity gives the picture a haunting, nagging persistence in one's mind, as if an answer to an equation is obsessively flashing onscreen sans the elements that yielded it. This forces us, in turn, to speculate endlessly about how this dysfunction came to exist.

Most interesting are the glimpses of noncommunication between D. and H. -- these two seldom seem on the same page, and indeed, much of the coherent discourse that passes between them happens through an intercom. Independently of whatever unspeakable tragedy struck these characters, husband and wife exist in radically misaligned interior worlds, as Hogg's occasional revelations of D.'s psyche capably demonstrate. In one scene, for example, D. dictates a fantasy into a tape recorder, rhapsodizing about an imaginary lover who satisfies her emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually, while erotically turning her inside out. In another, even more daring follow-up sequence, we take a visual excursion into D.'s oneiric life. The film temporarily assumes a drastically different aesthetic as the character fantasizes about a nighttime stroll through an amber-lit Vienna, with a street musician belching fire into the air through the bell of his tuba. But whereas D.'s inner self is voluptuous and sensual, H.'s couldn't be any more different: He perceives the world in very cut-and-dried, mechanical, and left-brained terms -- hence his creation of their home. Hogg paints D. as the central victim here, and there are mesmerizing scenes of her desperate and crushing attempts to try to reconcile her sybaritic needs with the mechanistic sphere that surrounds her -- as when she writhes against a wooden stool, bare flesh against wood -- futilely trying to meld the two in some elusive way. As you reflect on the disparity between these characters, the picture begins to take on allegorical connotations about the unbridgeable chasm between male inner life and female inner life, masculine creativity and feminine creativity.

Equally fascinating is Hogg's tone: Although the descriptions of this setup may sound achingly sad and depressing (and the movie feels that way in many sequences), a closer reading also reveals a sly, jet-black undercurrent of characteristically British levity -- as when Hogg places the slight, unassuming Albertine (cast against type, given her image as a former punk vocalist with the band the Slits) alone in the Melvin structure, and has her slink around through the hallways, opening and closing the closets with leering curiosity. The character's misalignment with her environs here isn't overtly funny, but it is wryly ironic and entertaining on that level.

Cinematically, this picture comes off as so unique that it almost seems insulting to discuss it intertextually, though the influences of several prior artists are apparent. In particular, the sight of Albertine creeping around the residence reminds one of a central image in French animator Jean-Loup Felicioli's 2006 short Bad Times. There are also overt echoes of Peter Greenaway, especially his 1987 film Belly of an Architect and his experimental 1980 drama The Falls -- the latter contains characters who, like D. and H. here, constantly drop vague references to some apocalyptic event that befell them in the recent past. Visually, there are also suggestions of the British artist David Hockney and his obsession with modernist styles -- especially one scene with blocking that echoes Hockney's 1971 painting "Mr and Mrs. Clark and Percy."

In the final analysis, this is not an easy film and it will almost inevitably alienate the majority of viewers. Yet it is a brilliant picture in its own way, and like Hogg's two prior features, affirms her as one of the most inimitable and fascinating directorial voices of the early 21st century.