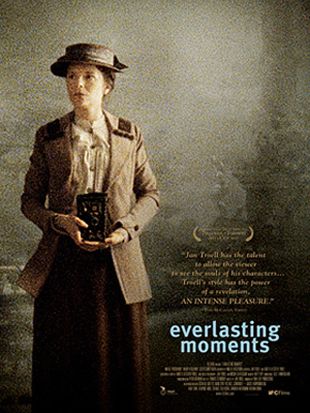

As a tale about Maria Larsson (Maria Heiskanen), a blossoming photographer at the turn of the 20th century, director Jan Troell's feature Everlasting Moments has an apt and clever title. The meaning is twofold: it refers to the central character's desire to capture "everlasting moments" with her camera, but the film itself also leaves its most indelible impressions on the audience as a series of striking visual and aurally enhanced moments that populate the screen only occasionally, standing out like embossments from the cold and repressed Scandinavian world that we are handed. The said images are manifold, from a canopied forest path with sunlight cascading through the far end, to the ominous shadow of a zeppelin slipping over a tall Swedish building, to (the film's best scene) torrents of rainwater gushing down a window and obscuring the countenance of Maria's adolescent daughter Maja's (the brilliant Callin Ohrvall) young boyfriend.

These visual tropes tie in beautifully to the theme of the film as well -- a woman's gradual process of coming into herself and gaining clearer perceptions of the world around her for the first time in 40 years. To be certain, the haunting and occasionally surrealistic visuals aren't consistently tied to the images Larsson herself produces with her camera, but the correlations between the visual shift in the film and the maturation of the character's perceptions are unmistakably present. The overall idea is that we seem to be gaining enhanced perceptions of the surrounding world along with Larsson, and that feels ingenious.

The problem with this approach, perhaps an inescapable one, is that it may risk deadening the audience for the first 45 minutes or so. For a time we may feel we're stuck with one of those foreign-language films that give foreign-language films a bad name, where costumed, emotionally repressed European actors tromp around on period sets in natural light and speak in slow, mannered dialogues. In truth, the film retains vitality from the very beginning -- vitality present in Maria Heiskanen's inspired performance and the glimpses of Larsson's inner life that the actress hands us. She may be fully oppressed by her abusive, ignorant drunk of a husband, Sigge (Mikael Persbrandt), and their claustrophobic house packed with children. Yet she shows us the torrents of emotion in her eyes, and in her trembling figure, with indignation that crescendos and eventually (especially in the later scenes) builds to a fever pitch. This culminates with the joy of artistic discovery, and also her righteous anger at her husband, who has absolutely no comprehension of her photography career and threatens to bring the whole thing crashing down.

The motion picture has at least two drawbacks, however. On a narrative level, Troell seems to occasionally take on more than he can handle; from time to time he leans toward an ensemble approach, with multiple, intersecting stories, but the film lacks the length to sustain this, so we are left with fragments of substories that never fully blossom. Just witness the suicide of one of Sigge's friends, who appears and disappears in the film so quickly that we have little idea of who he is or what he represents. The second major weakness is the fact that we never gain any satisfactory insights into why Larsson stays with such a vile husband, who puts her through a series of indignities including an offscreen beating, the repeated denigration of her photography career, an undesired pregnancy, and knife-wielding death threats. Troell implies that Larsson may be staying with her husband because of a deathbed request issued by her late father, but this simply doesn't suffice; it seems that she would inevitably leave the monstrous Sigge following the liberation dramatized in the film, and the writer-director owes the audience a more elaborate explanation for the permanence of the marriage. Fortunately, these lapses do not detract from the many pleasures of the film, including Troell's technical mastery and a series of proto-feminist themes made doubly fascinating given the period in which they are set.