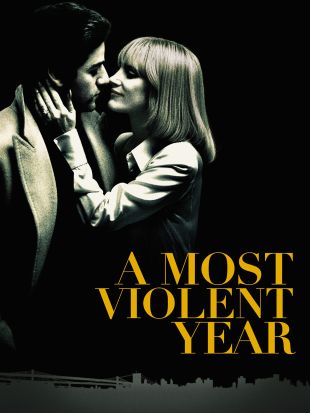

The titular annum of J.C. Chandor's evocative drama A Most Violent Year is 1981, a zenith period of crime and vice in New York City. Oscar Isaac stars as Abel Morales, an Hispanic-American fuel trader with serious designs on some dockside property that would give him unchecked access to the most cost-effective importing of overseas petroleum. He has married and started a family with the vampish Anna (Jessica Chastain), the daughter of a mafioso. Unlike his father-in-law, however, Abel long ago made a vow to himself to stay "clean" and eschew foul play and double-dealing. Matters soon grow more complex when some unsavory character -- presumably a competitor -- begins randomly hijacking his trucks mid-route, which makes it harder for Abel to stay above water without getting his hands dirty.

One sequence at the midpoint of this film particularly stands out: Abel hot-rods his sedan down a set of train tracks and into a concrete tunnel. He's tailing a criminal responsible for the serial robberies, and the light within the enclosure instantly darkens to such a degree that we can only identify the terrain about two or three feet in front of the vehicle. That's a critical scene not simply because it raises the movie to a high-wire climax and fully unveils an inner tension that has lingered sub rosa for the preceding hour, but because it provides an ingenious visual trope that sums up the whole drama. The central motif of the film is one of visibility. Chandor sets up this relatively straightforward story -- which owes an obvious debt to Coppola's The Godfather and Lumet's Prince of the City -- and interweaves the thread of a man semi-blindly feeling his way into a world of shaky corporate ethos that he doesn't yet fully comprehend, all while attempting to resist the seductive pull of corruption.

To nail Abel's myopia, the narrative essentially plays a series of games with the audience -- it functions as a long string of reveals. Time and again, we keep getting scenes that initially seem misguided at best, illogical at worst, yet deceptively so. In each instance, sans exception, Chandor then goes back and fills in the blanks with expositional information. Consider, for example, a development in which one of Abel's drivers is robbed and beaten within an inch of his life on a Manhattan freeway; he lands in the intensive-care unit of a local hospital, and then -- upon recovering -- climbs behind the wheel of one of Abel's trucks once again. We ask ourselves how he could be so ready and willing to get back on the horse, until we learn that the driver (a.) worships the ground that Abel walks on, and will do anything his mentor tells him, and (b.) has secretly packed a handgun to protect himself. Suddenly, it adds up -- but Chandor didn't give us the requisite insights until after the fact. As a screenwriter, he's like a jazz vocalist who deliberately lingers behind the beat with off-center phrasing, and then catches up in the final remaining seconds.

That all points to a central quality of Chandor's work: He's an innately gifted but heady director. We've known that since his debut Margin Call hit theaters in 2011, but he's never seemed as cerebral as he does in Year. As a result, the movie has a kind of icy cleverness, especially in the way it provides a conceptual metaphor for Abel's psyche. But by default, it keeps us two or three steps behind the action, to the point where we have to trust Chandor's instincts and avoid constantly second-guessing him. The narrative experimentation also has one key disadvantage: It robs the movie of a degree of emotional intensity that it might have otherwise possessed. Morales is clearly a Michael Corleone-inspired character -- his whole arc seems engineered to bring him to a point of helpless succumbing, as he's pulled into the cesspool of corporate devilry -- but unlike The Godfather, this film gets so wrapped up in narrative sleight of hand that any feeling of devastation takes a backseat. The iconic final sequence of The Godfather, in which Michael's underlings close the door on his wife Kay, brought home the horror of one man's inevitable moral and ethical demise. Here, we get an equivalent concluding scene, with a line that basically serves the same function: Abel's statement, "I've always done the right thing," is a shocker because we realize how ethically relativistic his definition of "the right thing" has become after he's endured so many calamities while trying in vain to stay righteous. In context, Chandor clearly intended that climactic line as a sort of gut punch, but it doesn't come off that way at all; in fact, it feels rather subdued. Nor does Abel's relationship with Anna build to the explosive catharsis that one might wish for.

Fortunately, though, the movie has much to compensate. In terms of the progression of Chandor's career, it seems not merely apropos, but arguably perfect. He began with Margin Call, a masterful look at the unchecked greed of Wall Street on the eve of the 2008 financial cataclysm, and then turned in a superb sophomore effort with 2013's All Is Lost, an ascetic, Old Man and the Sea-type story about a yachtsman (Robert Redford) struggling valiantly to save himself against increasingly slim odds. A Most Violent Year bridges the two stories: Abel fights like hell to keep himself afloat, but does so in the context of twisted capitalist chicanery.

Year has an intriguing layer of social commentary as well, and in that sense too it constitutes a forward stride for Chandor: In addition to telling the story of Abel, he wants to use the saga to dive into a very specific point in U.S. history -- the nexus between the 1970s fuel crisis and the greed of Reagan-era, white-collar excess. In this, he succeeds.

The movie's other great treasure -- heretofore unmentioned, but worth noting -- is its cadre of first-rate performances by the entire cast. Isaac and Chastain both do Oscar-caliber work, interpreting Abel and Anna as, respectively, a figure of quiet, brooding, commanding intensity, and a cauldron of suppressed vitriol and submerged demons. And Albert Brooks turns in a fine (if low-key) performance as the Morales' reliable and supportive attorney.

While it isn't a completely flawless drama, this picture nonetheless does achieve greatness and reconfirms Chandor as one of our most unique and compelling directorial voices.