Some stories lend themselves effortlessly to film, and Ben Mezrich's nonfiction tome Bringing Down the House: The Inside Story of Six M.I.T. Students Who Took Vegas for Millions marks no exception. Even the headlines engendered by this tale sang a biting, irreverent ode to the wiles of a half-dozen underdog coeds who managed to beat the evil "system" at its own game through sheer cunning and frightening intelligence. How can one make an unexciting film out of this material? In sum, one cannot; if a "foolproof" film story exists, this is it. It may be the most entertaining blackly comic anti-American fable since the Boyce-Lee account that inspired John Schlesinger's The Falcon and the Snowman. As a result, Robert Luketic's drama 21 (adapted, very loosely, from Mezrich's book) feels eminently thrilling and watchable almost by default. Never once does it fail to hook the audience. And yet, in retrospect, the film clocks in as a missed opportunity on many levels, with more than a handful of aching flaws.

Luketic qualifies as a competent journeyman director at best, and he's never even come close to topping the sugar-sweet whimsy of his underrated romantic fable Win a Date With Tad Hamilton! (2004). Here, his ham-fisted approach proves that he's absolutely the wrong person to helm this material (a fact evident as early as the disastrous prologue -- a bizarre, post-MTV whirlwind trip up and down the surfaces of CG-drawn gaming tables, where massive CG gaming chips fly across the screen). Luketic skirts through many sequences courtesy of flashy montages, pounding the audience repeatedly with blaring, deafening walls of music that bear no connection to the events onscreen, and images that do little to communicate anything of significance or even move the narrative forward satisfactorily.

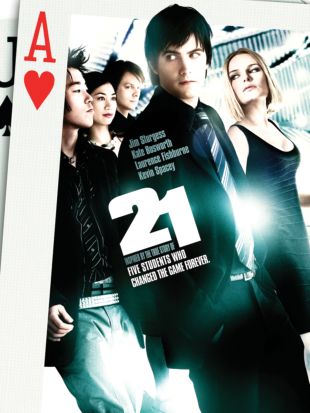

Preserving the approach of Mezrich's book, the Allan Loeb-Peter Steinfeld script makes a wise decision by honing in on a single protagonist -- Ben Campbell (Jim Sturgess as an ideally cast everyman). Steinfeld and Loeb immediately enable the audience to understand the universally empathetic motivations that would lure this straight shooter into an "underground" collegiate gambling ring: with an inability to make his dreams happen by paying for 300,000 dollars in tuition to Harvard Medical School, and a slim chance of landing a 1 in 78 scholarship that will give him a free ride to the said institution, does he have any other option? And could we feel any less than completely in synch with him? As Professor Micky Rosa, the leader of the said ring, Kevin Spacey achieves something close to perfection; drawing from some of the same cocky and intransigent notes that he sounded in Swimming With Sharks, and yet wrapping them in a veil of sly, unctuous, come-hither temptation, his Micky is a perfect Mephistopheles figure for these unwitting, impressionable, and deftly manipulated coeds.

The film scores a bull's-eye in its early passages as it sets up the logic for the events to follow, and Luketic and his production designers make an inspired decision by giving us an ontological environment where clandestine spheres (such as the nocturnal classroom where Professor Rosa "instructs," and a Chinese betting parlor that literally lies underground) seem to exist just beyond the confines of sunlit normalcy. The drama falters, however, once the students hit Vegas; if material such as this sings, we need to feel the lure -- the dirty, acid-infused kick -- of the gambling, along with Ben and his cohorts. Instead, the first several scenes in Glitter Gulch (in addition to feeling numbingly repetitive) have a limp, half-assed quality that bogs the film and the audience down. Never once do Luketic and his screenwriters pull the audience into the exciting gradual build of Ben & co.'s progressions from aspiring gamblers to instantaneous millionaires. (Most of the time, we aren't even sure how much they've accumulated, and throughout, Luketic skimps on one of the sauciest details -- the ensemble's employment of clever disguises to evade pit bosses.)

The film's second half seriously strains credibility. The surprises will not be disclosed here, but let it be said that Luketic and his screenwriters interpolate several twists and double-crosses that make the film feel like an ersatz, fifth-rate David Mamet thriller. It may have all happened exactly like this, but it rings false and seems to bear little correlation to real life. The film also suffers from a massive tonal problem in its second half. According to the book, these students got away with millions, but that isn't the impression that Luketic gives us at the conclusion. Instead, the director and screenwriter launder the ending by implying that the students (particularly the character of Ben) didn't really end up wrangling all that much from Vegas. We can recognize that implication as false from even the subtitle of Mezrich's book. Luketic is deliberately vague about the conclusion; he even spares us a final title card giving us the satisfactory knowledge of what happened to each character -- the saving grace in a movie like this.

The false implications of the concluding scenes are a real shame, because they defeat the film's ability to function as a guilty-pleasure thriller where we root for a bunch of underdogs who manage to screw the system from inside out and thwart the doings of the vile pit bosses. (We end up feeling that they haven't gotten away with anything.) At least the movie has the casino bouncers right; tonally, much of the tension in the picture originates via the enlistment of Laurence Fishburne, cast as Cole Williams, the head honcho at one of the Vegas casinos. As that character -- a great fire-breathing bull of a man who teaches card-counters a lesson by carting each one off to a subterranean warehouse, donning several gem-studded rings on one hand, and then viscerally beating each perpetrator within an inch of permanent brain damage -- Fishburne practically commands the production. Much of the first half of the movie does seem to be pointing to a tale in which a bunch of crafty students pull off a big one and, in the process, out-manipulate some thoroughgoing bastards who really deserve it. And up until the last 40 minutes, that's more or less what we get -- thanks in no small part to the loathsomeness of Fishburne's characterization and Sturgess' everyman affability.

But in the end, we're given an unsatisfactorily "moral" conclusion in which we don't even quite know what the moral is. (Don't manipulate Vegas casinos??) Moreover, the events of the last few scenes (which seem to negate everything that has preceded them) undercut our sense, throughout the movie, that Ben Campbell has benefited immensely from the casino experience -- both fiscally, and psychologically as well, by honing his identity and escaping from his lackluster life for the first time. That sudden contradiction is a difficult pill to swallow after watching the first two-thirds of this movie. In the final analysis, the prospect of watching this tale and remaining genuinely interested in the onscreen events may be an automatic, but this feels like yet another example of Hollywood's ultra-reactionary tendency to shy away from anti-establishment themes at the risk of offending or alienating part of the audience. Didn't they realize that the behavior of Cole Williams is offensive enough to sway just about everyone?