Charles H. Schneer was the unsung partner behind the fantasy films of stop-motion animation creator Ray Harryhausen. For 16 years, starting with It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955) and ending with Clash of the Titans (1981), the two generated some of the most enjoyable (and celebrated) science fiction and fantasy works to grace the big screen. And although Harryhausen, as the stop-motion expert and creator, received the lion's share of credit and adulation from fans, Schneer was also a creative partner in the team, in addition to overseeing the business end and most of the general production duties. Schneer was born in Norfolk, VA, in 1920, although he spent much of his youth in Mount Vernon, NY. He attended Columbia University and served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps Photographic Unit during World War II, during which he produced training films. He entered the movie industry by way of Columbia Pictures, and his earliest official credit there was as associate producer on the espionage thriller The 49th Man (1953), which was directed by Fred F. Sears (who later helmed Earth vs. the Flying Saucers), under the auspices of low-budget producer Sam Katzman. It was a friend from his years of Army service who also knew Harryhausen, who introduced the two in 1954. As both of them had been involved with the making of training films for the armed forces, they had that relatively recent piece of personal history in common, and soon found that they thought along the same lines about potential film projects. Schneer moved up to a full producer's credit on Harryhausen's first Columbia film, It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), directed by Robert Gordon, which was an uncommonly well-made science fiction thriller, making careful and clever use of standing sets for its atomic submarine interior and even better use of stock footage and second-unit material, which only enhanced the special effects sequences, which were all the more challenging as they involved a multi-armed sea creature and sequences set in and around water (which is very difficult to animate).

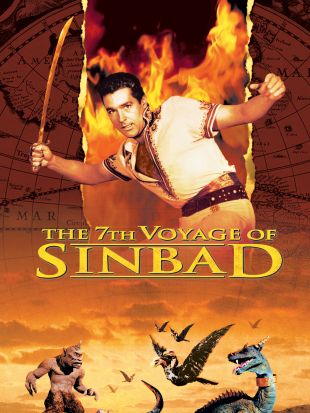

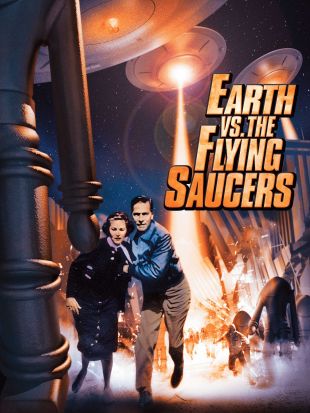

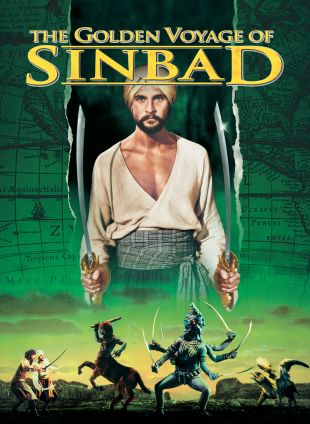

Schneer's first film withHarryhausen was a success, and the producer was responsible for bringing in the newspaper articles that led to their next movie, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), which carried stop-motion animation into wholly territory, again successfully. Schneer proved to be the opposite of most producers in the 1950s; he watched the bottom line, of course, but he was always encouraging Harryhausen to think of new directions for his work and to go beyond existing boundaries rather than limit work to the previously understood restrictions of imagination and budget. Harryhausen has also described him as an important contributor of ideas to their work. By 1957, they'd ceased working under Katzman and set up Morningside Productions, through which both men would retain a measure of control of their work (and also a share of revenue, with Harryhausen credited as associate producer as well as special effects creator and designer). After one more science fiction movie, 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), they took the next step, into the realm of Arabian Nights fantasy -- a pet subject area of Harryhausen's since childhood -- and into color shooting, with The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). That was also the movie that brought Bernard Herrmann into the creative mix, resulting in the first of a string of four classic fantasy film scores composed for Harryhausen's movies. Harryhausen and Schneer decided with that film to abandon the simpler science fiction thrillers -- and what the animator has called monster-on-the-loose stories -- in favor of bolder, more creative, and fantastic stories involving mythology and works of imagination out of the literary past. The results included The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1960) (which led to a pilot episode for a proposed television series, produced by Schneer), Mysterious Island (1961), and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Their creative sensibilities often led them into unexpected realms of fantasy filmmaking, as with The First Men in the Moon (1965), an adaptation of an H.G. Wells story that reconciled the author's decades-old fiction with the reality of the modern space program.

In between his work with Harryhausen, Schneer also found time to work on other movies, as post-production frequently took many months as the stop-motion work was devised and completed. The results, even there, were some pretty fine little dramatic films separate from Harryhausen: The World War II dramas Hellcats of the Navy (1956) (the only movie in which Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan ever starred together), Tarawa Beachhead (1958), and The Battle of the Coral Sea (1959) and the crime drama The Case Against Brooklyn (1958), the psychological western Good Day for a Hanging (1959), and the biographical film on Werner Von Braun, I Aim at the Stars (1960). Schneer moved to London in 1960 in the wake of the first two color films he produced. The British film industry had perfected a variation on blue-screen effects that enhanced stop-motion work and also made color filming uniquely practical, and England remained his home for the next 45 years. During the 1960s, as the Harryhausen movies grew in budget and complexity, he fit fewer outside projects in around them, but still managed to produce the costume drama Siege of the Saxons (1963), the adventure yarn East of Sudan (1964), the swinging London comedy You Must Be Joking! (1965), and Land Raiders (1969). These pictures often involved directors, creative artists, and crew members who were associated with the Harryhausen movies, including director Nathan Juran (who did pictures with Schneer for well over a decade) and composer Laurie Johnson. As time went on and their brand of fantasy films became supplanted by more elaborate and slickly made science fiction (and space fantasy works such as Star Wars and its successors), Schneer and Harryhausen found it harder to interest studios in their work. Their longtime relationship with Columbia Pictures ended after Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977), and their next film, Clash of the Titans (1981), was an MGM production. It was also their last. Studios were more interested in financing computer-generated special effects, and Harryhausen's stop-motion work seemed both quaint and unnecessarily expensive (unless one saw a point to it, as millions evidently still did, based on video sales of their classic films). Schneer retired in the 1980s, although he kept an office in London well into the 1990s, and was still active with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences into the early twenty-first century. He returned to the United States in 2005 and passed away in early 2009.