Thanks to the content of his films, American director James Ivory has spent much of his long career being mistaken for an Englishman. Few filmmakers have been more closely associated with a particular type of genre than Ivory and his longtime collaborator, producer Ismail Merchant. The very mention of the hyphenate Merchant-Ivory effortlessly conjures up heavily stylized images of Edwardian England, replete with stiff upper lips, effete aristocrats, and young women confined by both corsets and repressed desire. However, although much of Ivory's reputation has been built on his E.M. Forster-adapted period dramas, he has also earned considerable respect for the insightful examinations on the interplay of different cultures inherent in almost all of his work -- particularly his earlier films about India -- and his and Merchant's ability to make quality films on a minimal budget.

Born in Berkeley, California, on June 7, 1928, Ivory grew up in Klamath Falls, Oregon, where his father ran a sawmill. Having decided at the age of 14 that he wanted to go into film as an art director, he attended the University of Oregon, where he majored in fine arts. Following graduation, Ivory traveled to Tours, France, to study the language, but he soon lost interest in his studies. He relocated to the University of Southern California, where he entered the film department. It didn't take Ivory long to realize that he hated film school, so he took a leave of absence to travel to Venice, where he worked on his masters thesis, Venice: Themes and Variations. However, his work was interrupted by the Korean War, for which he did two years service in Germany; his time there was mainly spent putting on Soldier Shows, which, as he would later remark, gave him his introduction to show business.

While working on Venice, a 28-minute documentary that juxtaposed contemporary views of the city with paintings by the masters, Ivory was introduced to art from India's golden age. His ensuing fascination with the country's culture was manifested in his next film, a documentary on Indian artifacts called The Sword and the Flute (1959). The film was hailed by a number of critics, as well as New York's Asia Society, and it was during a visit to New York for a screening of the film that Ivory met Ismail Merchant. A young Indian who had been sent to the United States for business school, Merchant was passionate about film. He and Ivory became fast friends, and in 1961 they formed Merchant Ivory Productions. The two also became acquainted with novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala around this time; Jhabvala would become irrevocably associated with the two, acting as the screenwriter for all but a handful of their films.

The trio's first films were set in India, dramas concerned with questions of cultural interplay, personal identity, and physical and emotional isolation. All of these films were made independently (only one, the poorly received The Guru (1969), has been made for a studio during the course of Merchant and Ivory's years together), and ably demonstrated the kind of technical expertise the filmmakers were capable of achieving with a very limited budget. Their first film, The Householder (1962), was an adaptation of a novel by Jhabvala about an Indian couple experiencing the travails of an arranged marriage. It was shot in black and white by Subrata Mitra, otherwise known as Satyajit Ray's cameraman; Ivory had befriended Ray, who reportedly acted as the film's uncredited editor and music supervisor.

Shakespeare Wallah (1965), the trio's second film, was the one that first gave the filmmaking team international recognition. A sensitive, thoughtful portrayal of a family of English actors traveling through India, it helped to establish Ivory as a director adept at capturing particular moods through visual representation, much in the style of Ray or Jean Renoir. The film was a critical and financial success, winning an award at the Berlin Film Festival and grossing four times what it cost to make.

Following the disastrous The Guru (1969) (a production reportedly ill-fated from start to finish) and Bombay Talkie (1970), Merchant-Ivory relocated to the wilds of upstate New York for Savages (1972). A black and white allegory about the nature of modern "civilization," it represented a complete departure from Ivory's earlier work. The film received mixed reviews, all of which were incredibly favorable when compared to those that greeted Ivory's next effort, The Wild Party (1974). Based upon the infamous Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle/Virginia Rappe case, the film was such a badly edited mess that Ivory subsequently disowned it.

Roseland (1977), a series of vignettes set in New York's legendary dance hall, saw Ivory back in form, and it received a standing ovation when it premiered at the 1977 New York Film Festival. The film was praised for the sort of naturalism and keenly portrayed sense of isolation apparent in Ivory's earlier films about India. It was followed by another widely praised Indian excursion, Hullabaloo over Georgie and Bonnie's Pictures (1978), and then by a 1979 adaptation of Henry James' The Europeans. A richly detailed picture that maintained an intense -- some would say exhaustive -- faithfulness to the book, The Europeans was the sort of literary adaptation with which Merchant-Ivory would become synonymous. After Quartet (1981), which was based upon the relationship between Jean Rhys and Ford Madox Ford, and Heat and Dust (1982), adapted from Jhabvala's Booker Prize-winning novel, another James adaptation, The Bostonians, followed in 1984. A love triangle set against the backdrop of the early stages of the suffragette movement, it featured another strong script by Jhabvala, minutely detailed period authenticity, and an Oscar-nominated performance from Vanessa Redgrave.

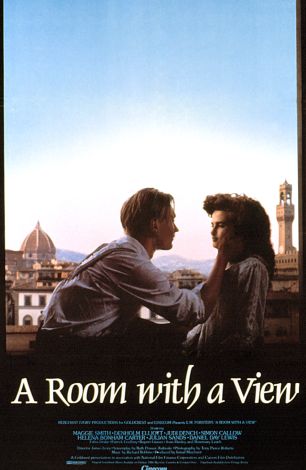

Although The Bostonians was moderately successful, Ivory's reputation was sealed the next year with his adaptation of E.M. Forster's A Room with a View. A romantic comedy set during the Edwardian period, it was a lush, witty affair, one that proved to be enormously popular with critics and audiences alike. Nominated for eight Academy Awards (it won three, including Best Adapted Screenplay for Jhabvala), it was praised for its beauty and its fidelity to the spirit (and content) of Forster's novel. Another Forster adaptation, Maurice, was released the following year. Taken from Forster's posthumously published novel about homosexual love during the early 1900s, it earned a respectable amount of praise, although a number of critics felt that Ivory's extraordinary adherence to the novel made for a painfully long, slow film.

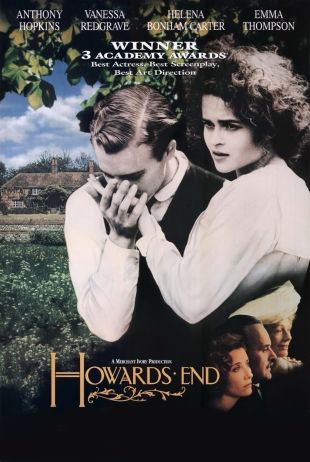

Ivory's third Forster excursion, the 1992 Howards End, was undoubtedly his most accomplished film to date. Another exploration of the repercussions of class collision in the early part of the 20th century, it featured gorgeous detail (made all the more remarkable by a modest budget) and all-around stellar performances from the likes of Anthony Hopkins, Vanessa Redgrave, and Emma Thompson, the last of whom won a well-deserved Oscar for her work. In total, Howards End earned nine Oscar nominations, including one for Best Director, and a multitude of international honors.

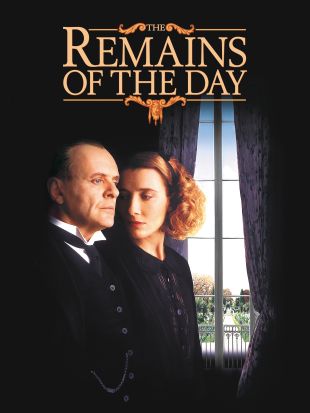

Ivory's next film, The Remains of the Day (1993), also earned a lavish dose of critical acclaim. Adapted from Kazuo Ishiguro's novel about an emotionally stunted butler (superbly played by Anthony Hopkins) who refuses to admit his love for a housekeeper (another great performance from Thompson) or the error of his employer's ways, the film was essentially an emotionally wrenching character study. It earned a number of international award nominations, including Oscar nominations for Thompson, Hopkins, Jhabvala, and Ivory.

Ivory subsequently turned away from literary adaptation, though he remained immersed in the period drama genre. Jefferson in Paris (1995), which proved to be a substantial disappointment, focused on the public and personal affairs of the American President, while Surviving Picasso (1996) -- which also failed to draw critical or commercial favor -- was a detailed epic about Picasso and his long-suffering lovers. In 1998, Ivory ventured into a more modern milieu with A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries. Based upon a novel by Kaylie Jones, the daughter of novelist James Jones, the film was a poignant study of an expatriate family straddling two worlds (Paris and the U.S.) and coping with change and alienation. Ivory's most celebrated film since The Remains of the Day, it combined a sterling lead performance by Leelee Sobieski with the director's usual talent for graceful, studied detail.