Fannie Hurst was one of the most popular novelists in America from the 1910s through the 1940s, and saw dozens of films made from her books and stories. One of the foremost Jewish-American writers of her generation -- alongside her almost exact contemporary, Edna Ferber -- Hurst's work captured elements of lower- and middle-class urban life, especially among ethnic and racial minorities that had previously been overlooked by American authors. Fannie Hurst was the daughter of Samuel Hurst and the former Rose Koppel. Born in Hamilton, OH, she was raised in St. Louis, MO, where her family led a difficult existence, owing to her father's problems as a businessman. Tragedy and bankruptcy seemed to hang as a threat over the head of the family in perpetuity; she lost a sister to diphtheria in 1889, and the Hursts lived in 11 different homes between 1885 and 1901. She graduated from Washington University and moved to New York City in 1909 to attend Columbia University.

Hurst blossomed creatively in New York and began writing stories in 1912. She quickly established herself as a strikingly new literary voice, her work focusing on the lives of poor and working-class women and families, particularly those in department stores, the garment district, and design houses, popularly known as the "rag trade." Her stories began coming to the screen in 1918, but the first notable film based on any of Hurst's fiction was Frank Borzage's 1920 adaptation of her book Humoresque, about a boy who works his way out of New York's slums and into the circles of the wealthy and powerful. The subject matter proved extremely controversial for its producers -- according to author Kent Jones, the plot and setting of life on New York's Lower East Side was described as being far grittier than Adolph Zukor, the head of the distribution company handling the movie, had wanted or expected. Jones quotes a Zukor-authored memo to screenwriter Frances Marion stating: "If you and Fannie Hurst are so determined to make the Jews appear sympathetic, why don't you choose a story about the Rothschilds or men as distinguished as they?" Three years later, Borzage enjoyed even greater success when he brought another of Hurst's stories (also adapted by Marion), The Nth Commandment, dealing with department store workers, to the screen.

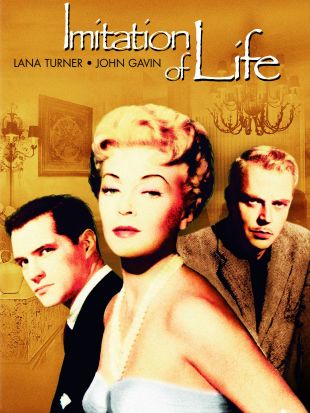

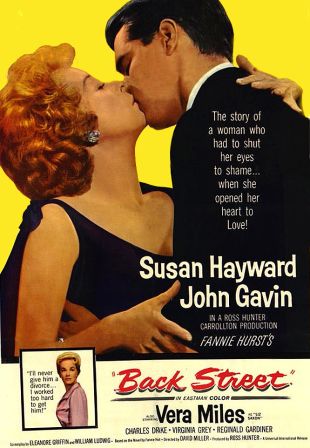

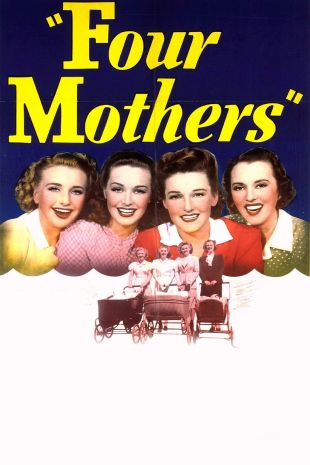

From 1918 through 1961, 29 movies were adapted from Hurst's stories and novels -- several, including Humoresque, Back Street, and Sister Act, more than once -- of which the most well remembered today are the two screen versions of Imitation of Life, from 1934 and 1959, respectively. Since the 1950s, Hurst's work has come to be regarded as glorified soap opera. Typical is Symphony of Six Million, about a young Jewish doctor who abandons his slum origins and moves to Park Avenue, only to face a deep personal crisis over the death of his father. It was filmed in 1932 and was something of a rarity as a major Hollywood movie that focused on a Jewish-oriented story (a subject category that Hollywood tended to avoid); its mere production speaks volumes about Hurst's influence and popularity. Some of her peers resented Hurst, her stories, her style of writing, and most of all, her success, even in her own time. Critic Daniel Mangin, writing in The New York Times in 1999, cites F. Scott Fitzgerald in his book This Side of Paradise as naming Hurst as an author who hadn't produced a single story "that would last ten years." The movie adaptations, at least, proved Fitzgerald wrong, especially the novel Sister Act, which would serve as the basis for four major films: Four Daughters (which served as John Garfield's screen debut), Four Wives, Four Mothers, and Young at Heart, from the 1930s through the mid-'50s.

Critics on the political left also resented Hurst, not only for her commercial success but also the nature of her writing; by giving lower-class and working-class readers a sense of dignity over their day-to-day achievements, it was felt that writing like hers served to infuse a potential source of political and economic unrest. Despite those criticisms, she was an activist for political and social justice, and not just in her writing. Through her friendship with the African-American author Zora Neale Hurston (whom she also employed briefly as a secretary), and later with Eleanor Roosevelt, Hurst became strongly identified with the struggle for civil rights from the 1920s through the 1960s. Some of her portrayals of African-American life and characters might seem dated to modern sensibilities (even Langston Hughes couldn't resist satirizing Imitation of Life, which is itself a measure of Hurst's popularity and importance), but those same portrayals were major breakthroughs in the popular perceptions of readers, in an era when readers mattered in shaping public opinion and politics. Her work also showed surprising durability -- Imitation of Life was adapted suitably into a late-'50s drama by director Douglas Sirk that was very much on target, despite the novel's origins in the early '30s. Hurst's work has largely been out of circulation since the late '60s, though some of the movie adaptations -- most notably Sirk's 1959 Imitation of Life (which many African-American women too young to have seen it in theaters love) -- have retained significant audiences and critical respect. Since the mid-'90s, she has begun to attract some interest among scholars of American literature and Jewish-American culture, and in the 21st century, her work is ripe for rediscovery by feminist cultural historians.