Steve Fisher was a key figure in the development of film noir as a Hollywood genre, and one of the most important and influential screenwriters of the 1940s. Born Stephen Fisher in 1912, he was established as an author of short fiction by the time he was in his mid-twenties, including My Heart Sails Tomorrow, a mystery story in Liberty Magazine, and Shore Leave, which appeared in Cosmopolitan, and which he later transformed (in collaboration with Harvey Harris Gates) into the screenplay for Navy Secrets (1939). Fisher broke into films at Universal with the story for The Nurse From Brooklyn (1938), and he later wrote screenplays for Monogram and Paramount. Fisher's big break came, however, when his novel I Wake Up Screaming was purchased by 20th Century Fox and adapted by Dwight Taylor into the screenplay for the film of the same title, which is generally regarded as Hollywood's first film noir. H. Bruce Humberstone's I Wake Up Screaming was a stylishly dark thriller mixing romance and an unsettling mood of lurking doom on several levels into a compelling whole -- the film was actually somewhat less ominous in tone than Fisher's book, but it still established the film noir genre in American cinema. I Wake Up Screaming (which was issued at one point with the less jarring alternate title "Hot Spot") was not only a hugely popular success, as an unusual vehicle for Victor Mature, Betty Grable, and Laird Cregar, but it also opened up a whole new genre of psychologically centered crime thrillers, and also became one of the most heavily studied movies of its era. Fisher was next responsible for the screenplay of Fox's Berlin Correspondent (1942), a belated anti-Nazi thriller, and the flag-waving morale-boosting action-drama To the Shores of Tripoli that same year. The best of Fisher's wartime work was the screenplay (written in collaboration with future blacklistee Albert Maltz) for Destination Tokyo (1943), an epic-length submarine thriller starring Cary Grant. In 1945, Fisher and Frank Gruber would successfully adapt Charles G. Booth's novel Mr. Angel Comes Aboard into the screenplay for Johnny Angel, one of RKO's biggest hits of the year.

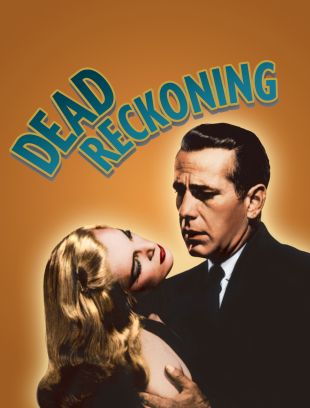

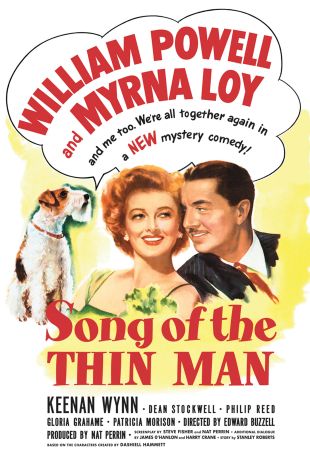

Fisher returned to the field of film noir in 1946-1947 with a series of beautifully wrought scripts that represented his most productive period in Hollywood. His script for the genre classic Dead Reckoning (1947), directed by John Cromwell and starring Humphrey Bogart and Lizabeth Scott, was, at once, one of the most beautifully stylish and disturbing crime dramas of the period, filled with notably grisly snatches of dialogue worked offhandedly into the standard banter of these underworld/mystery thrillers, and nasty action (mostly involving fire), as well as hints of very dark psychology at work, even in the mind of the hero. He also wrote the screenplays to such notable low-budget efforts of the period as the Monogram drama The Hunted (1947); and he did the scripts to a pair of MGM classics, Robert Montgomery's dazzlingly experimental Lady in the Lake (1947), based on the novel by Raymond Chandler, and Edward N. Buzzell's moody, dark detective thriller Song of the Thin Man (1947), which closed out the long-running film series on a fascinating and compelling note. Those two films marked the pinnacle of Fisher's career in Hollywood in terms of prestige.

For the next few years, most of Fisher's best work involved screenplays with dark twists in their action and characters, for major and minor studios alike, including the Cornell Woolrich adaptation I Wouldn't Be in Your Shoes (1948) at Monogram; the postwar drama Tokyo Joe (1949), starring Humphrey Bogart, at Columbia; Roadblock (1951), starring Charles McGraw, at RKO; the Anglo-American production The Lost Hours (1953); John H. Auer's bizarre and engrossing police thriller The City That Never Sleeps (1953); and Allan Dwan's offbeat Western The Woman They Almost Lynched (1953). He also wrote a few relatively conventional screenplays in other genres, including the navy epic Flat Top (1952), and even co-authored a stage play, Susan, with comedy veteran Alex Gottlieb, that became the basis for the romantic cinematic romp Susan Slept Here (1954), starring Dick Powell. In his prime years, Fisher's best work, which essentially means his film noir scripts -- regardless of which studio they were shot at, which director brought them to the screen, or which actors were in them -- all have a dreamlike feeling to their action and dialogue, as though one or more of the participants (and perhaps even the audience) is in some psychological state removed from conventional reality; the result is an unsettling feeling of something being quietly, terribly wrong as it unfolds, yet is also so compelling that audiences could seldom tear themselves away from one of his stories or scripts, once a movie started. His career slowed down at the end of the 1950s, and his influence seemed to fade with the end of the era of low- to moderately budgeted thrillers. Fisher was involved in writing on the 1960 series Checkmate, created by his fellow mystery author Eric Ambler, but in movies his work was mostly confined to Westerns, principally for producer A.C. Lyles, on the latter's films built around veteran genre stars. Fisher contributed scripts to the television series Cannon and Kolchak: The Night Stalker during the 1970s, and wrote screenplays for a handful of made-for-television productions including one notable Western, The Last Day (1975), before retiring. Among his novels, I Wake Up Screaming remains his most famous and most often reprinted work, but his other titles, principally in the mystery field, include Take All You Can Get, Image of Hell, Giveaway, The Big Dream, Homicide Johnny, The Night Before Murder, No House Limit, The Sheltering Night, Be Still My Heart, Winter Kill, and The Hell-Black Night. The latter was adapted into a movie, Woman in the Rain, in 1976, just four years prior to Fisher's death. Later adaptations of his work, including a 1953 remake of I Wake Up Screaming entitled Vicki, all seemed to suffer from a lack of sympathy on the part of directors, designers, and actors, who just couldn't get inside of his work and the motivations of his characters the way filmmakers, production crews, and actors had during the 1940s. Although Fisher didn't contribute to any major films after the 1950s, his influence is still felt today among younger screenwriters and directors, principally through I Wake Up Screaming and its 1941 Fox film adaptation, and his work as a screenwriter on a handful of highly respected examples of 1940s film noir.