The father of montage, Russia's Sergei Eisenstein was one of the principal architects of the modern cinematic form. Despite a relatively small ouevre of only seven completed films, most if not all of which suffered under the weight of communist intrusion, few individuals were more instrumental in enabling motion pictures to evolve beyond their origins in 19th century Victorian theater into a new arena of abstract thought and expression. While later criticized for the strong currents of propaganda coursing through his work, the continuing influence of Eisenstein's films is, regardless of politics, undeniable; a master of metaphor and allusion, he brought to the medium a new depth of power and complexity.

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was born January 23, 1898, in Riga, Latvia. The child of an affluent architect, he studied at the Institute of Civil Engineering in Petrograd, and in the wake of the 1917 revolution he began working as an engineer for the Red Army. By the early '20s, he had become the set designer of Vsevolod Meyerhold's Moscow Proletkult Theater, later graduating to the position of director; there he learned the principles of "bio-mechanics," or conditioned spontaneity. Eisenstein's interest in film began with an appreciation of the work of D.W. Griffith, whose editing style influenced him in the production of his first cinematic endeavor, the 1923 five-minute newsreel parody Dnevnik Glumova. A stint with Lev Kuleshov's film workshop followed, as did an increasing fascination with the burgeoning avant-garde.

With his feature debut, 1924's Stachka, Eisenstein introduced a new kind of film language, dubbed "montage." Expanding upon Meyerhold's theory of bio-mechanics, montage consisted of a sequence of conflicting images which served to abbreviate time spans and overlap symbolic meanings, with the cumulative emotional effect of a scene greater than the sum of its parts. Theorizing that it worked in a fashion similar to the dialectic of Karl Marx, Eisenstein sought to use the montage technique to make films for the common man; in the film's most memorable sequence, a group of factory workers are shot down, with the scenes of their deaths intercut with the depiction of cattle at the slaughter -- parallel images trading on the emotional impact of each other to heighten their combined impact.

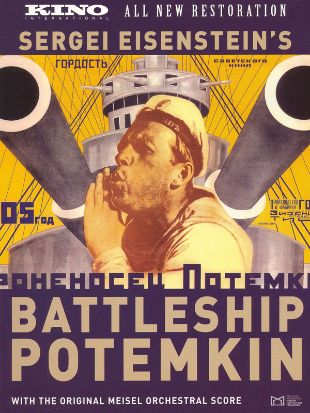

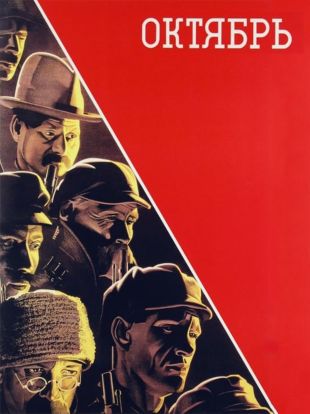

Eisenstein's second film, 1925's massively influential Battleship Potemkin, further honed the montage concept. The much-imitated "Odessa Steps" sequence, in particular, proved so powerful that many audiences believed they were viewing actual newsreel footage, prompting a pleased Eisenstein to label himself an "illusionist." For the follow-up, he was commissioned to direct 1927's Oktiabr in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution. Communist officials, already wary of the impact of his work on audiences, forced Eisenstein to temper his montage style, although the film clearly remains the product of his distinctive vision. Generalnaya Liniya, his final silent film, premiered in 1929.

At the dawn of the 1930s, Eisenstein was sent to Europe and the U.S. to research the sound-film phenomenon. Greeted by the global movie community as a great hero, he was befriended by the likes of Albert Einstein, Abel Gance, Charlie Chaplin, Walt Disney, and his hero, D.W. Griffith. Encouraged by documentary pioneer Robert Flaherty to explore Latin America during his journey, he shot Que Viva Mexico in 1930 with the financial assistance of writer Upton Sinclair. Upon completing the principal photography, Eisenstein sent the completed footage to Russia, where it was intercepted by government officials and removed from the director's control.

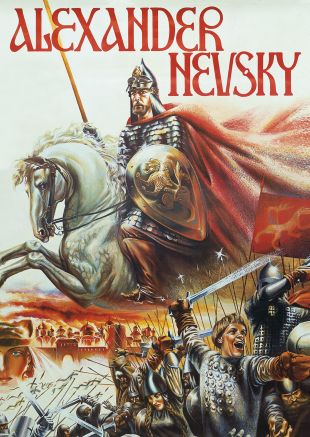

In 1932, Eisenstein was named a scholar of the Moscow film school, where he wrote a number of essays about montage and motion picture direction which were later published in book form. In 1935 he began filming Bezhin Lug, but the screenplay's bitter political commentary brought the wrath of Party officials, who shut down production prior to the picture's completion. Only by submitting to a public apology was he allowed to begin work on 1938's Aleksandr Nevsky, an attack on Nazi Germany later withdrawn from distribution after Josef Stalin signed a 1939 non-aggression pact with Adolf Hitler.

In 1945, Ivan Grozny I, the first film in a projected trilogy documenting the life and times of the notorious 16th century czar, appeared to great acclaim within the Soviet Union; however, the second chapter's 1946 completion was met with the furor of Stalin, who so despised the picture that he effectively buried it until 1958. Ironically, Stalin nevertheless agreed to allow Eisenstein to film the trilogy's conclusion, but health problems forced the director off of the project before it could be completed. Sergei Eisenstein died of a heart attack in Moscow on February 11, 1948.