Once the vanguard of 1960s-1970s Hollywood New Wave, director Arthur Penn saw his cinematic fortunes decline with the mid-'70s rise of more straightforward blockbuster entertainment. Even as he struggled through the '80s and '90s, however, Penn's legacy was assured by such films as Little Big Man (1970), Night Moves (1975), and the pivotal masterwork Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Born in Philadelphia, Penn was trained to follow in his father's footsteps as a watchmaker, but by high school, he knew he preferred theater. While stationed at Fort Jackson, SC, during World War II, Penn formed a small drama circle with his fellow infantrymen, and continued his education as an actor at school in North Carolina and Italy after the war. Though Penn acted in Joshua Logan's theater company and studied with Michael Chekhov at the Actors Studio's Los Angeles branch, he opted for a career behind the scenes when he got a job at NBC TV in 1951. By 1953, Penn was writing and directing live TV productions for the Philco Playhouse and Playhouse 90. Earning a shot at feature films, Penn combined the Method acting concentration on character psychology with the story of legendary Western outlaw Billy the Kid in The Left-Handed Gun (1958). Starring Paul Newman as Billy and shot in crisp black-and-white, The Left-Handed Gun emphasized '50s rebel neuroses over pastoral spectacle, becoming more of a character study of youthful revolt spiked with dramatic violence than a typical good vs. bad oater. Though European audiences loved it, Americans were unimpressed. Having directed the Broadway success Two for the Seesaw that same year, Penn stuck with theater and quickly established a sterling reputation with consecutive Broadway hits: The Miracle Worker, Toys in the Attic, and All the Way Home.

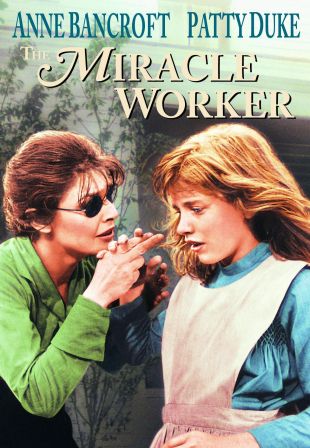

Penn returned to movies with the film adaptation of The Miracle Worker (1962). Resisting pressure to cast Elizabeth Taylor, Penn insisted that Anne Bancroft and Patty Duke reprise their stage roles as intrepid tutor Annie Sullivan and her blind and deaf charge Helen Keller. Saccharine-free and masterfully acted, The Miracle Worker became a hit, earning an Oscar nomination for Penn and Oscar wins for Bancroft and Duke. Penn's Hollywood glow quickly diminished, however, when star Burt Lancaster abruptly fired Penn two days into shooting on The Train (1964). Angry and undaunted, Penn proceeded to make the underrated and little seen Mickey One (1965). Shot with French New Wave aplomb and starring Warren Beatty, Mickey One eschewed all narrative certainty in its highly personal exploration of a nameless man's paranoid flight from the Mob, presaging the enormous influence New Wave technical freedom, genre revision, and ambiguity would have on Hollywood a few years later. Penn left filmmaking again in disgust after producer Sam Spiegel fired him from The Chase (1966) and recut the film.

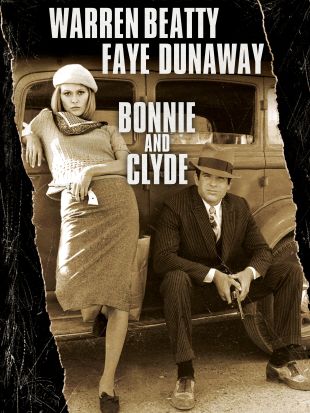

After a year off, however, Penn was coaxed back into movies by Beatty to helm Bonnie and Clyde. Though they clashed during production, Beatty saw to it that he and Penn could cast the film with unknowns from New York theater and TV, shoot with no studio interference on location in Texas, and edit the film in New York. With his producer-star's full support, Penn aimed to make the violence as brutal as possible, culminating with the incendiary quick-cut, slow-motion climax showing the eponymous glamour outlaws riddled by bullets. Though critics were repulsed by the bloodshed and the notion of criminals as beautiful doomed heroes, Beatty, armed with a rave by Pauline Kael and reports of audience enthusiasm, fought Warner Bros. for a re-release and Penn's combination of French New Wave style with an American genre finally made an impact. Hailed as a visionary work and embraced by the youthful Vietnam-era audience, Bonnie and Clyde became a pop-culture phenomenon, inspiring a cycle of revisionist gangster movies that included Thieves Like Us (1974) and Badlands (1973), making stars out of Faye Dunaway and Gene Hackman, and altering the visual language of Hollywood violence. Penn lost the Best Director Oscar, though, to The Graduate's (1967) Mike Nichols.

Penn confirmed his place in the new Hollywood counterculture firmament with Alice's Restaurant (1969) and Little Big Man (1970). Adapted from Arlo Guthrie's song and starring Guthrie, Alice's Restaurant was a dreamy, satirical, fun, yet downcast look at life in a hippie commune that garnered Penn his third Oscar nod for directing. More epic in form and content, Little Big Man mordantly re-framed the glorious myth of the Western frontier as a tragic comedy of genocide and white stupidity and amorality. Though star Dustin Hoffman's misadventures as a snake oil salesman, gunfighter, and adopted Cheyenne provided comic relief, Penn's tough depiction of the Washita Massacre and different take on Custer's Last Stand powerfully revealed which side was "civilized." Though Little Big Man was a major hit, Penn took a hiatus from films (save for the omnibus documentary Visions of Eight [1973]) until Night Moves (1975). As with The Long Goodbye (1973) and Chinatown (1974), Night Moves recast the potent film noir detective as a man overwhelmed by the corruption he uncovers. Despite the presence of Gene Hackman as the doomed PI, Night Moves' rigorously downbeat tone was no longer in synch with audience tastes. Penn's next effort, The Missouri Breaks (1976), was intended to be a blockbuster pairing of Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando as a horse thief and the gunfighter hired to kill him. Though Brando and Nicholson made a fascinating pair, the film's shifting tones and defiant eccentricity turned off audiences and critics. Penn didn't direct another film until his critique of the 1960s, Four Friends (1981).

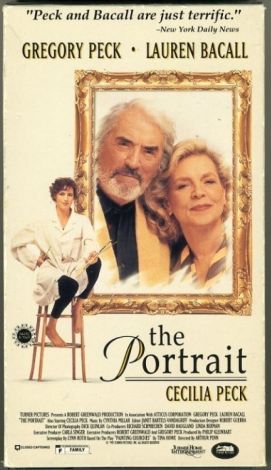

Never able to recapture his late-'60s success, Penn directed only the workmanlike spy actioner Target (1985) and thriller Dead of Winter (1987) before the barely released Penn & Teller Get Killed (1990) essentially ended his feature-film career. Returning to the more welcoming environs of TV, Penn scored a critical success with The Portrait (1993), a finely crafted character study starring Gregory Peck and Lauren Bacall. The made-for-cable feature Inside (1996) dealt with the kind of politically charged subject matter -- in this case, South African apartheid -- reminiscent of Penn's best films. Though he was long past retirement age, Penn, via his director son Matthew Penn, signed on as an executive producer for Law & Order's 2000 season to help punch up the long-running series' New York grit; a skill he exercised again helming an episode of Sidney Lumet's cable series 100 Centre Street (2001).