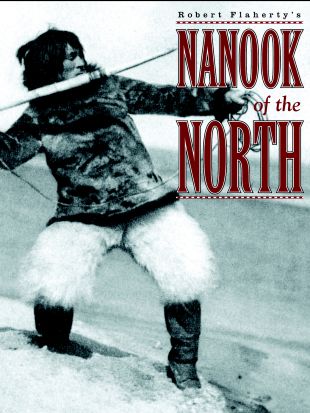

Michigan-born filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty was the son of a miner/prospector who dragged his son along on his many wealth-seeking expeditions to northernmost America. Thus the young Flaherty was exposed to many different cultures. As an adult, Flaherty offered his services as an explorer, guide and "native" specialist (though he reportedly despised that condescending word and avoided using it). From 1910 through 1916, he handled numerous expeditions into the Canadian wastes and wilderness on behalf of Sir William McKenzie, the builder of the Canadian Northern Railway. Allegedly it was McKenzie who suggested that Flaherty record his explorations on film. While fiddling with his camera out of boredom, Flaherty discovered that the Hudson Bay Eskimos, for whom he acted as interpreter, were natural and willing movie subjects. After several false starts, he produced his first feature-length record of Eskimo life, Nanook of the North, in 1922. His backers were the Revillon brothers, who hoped to use the film to promote their fur business. While he claimed to disdain "showmanship," Flaherty was not above a little fakery in getting the best effect; Nanook's igloo is patently fake, while the famous harpooning sequence was comprised of several different harpooning expeditions filmed over a series of days. Nonetheless, Nanook was an impressive achievement, and though it was not (as has often been claimed) the first feature-length "true life" film ever made, it was the first big box-office success of its genre.

Four years after Nanook, Paramount Pictures commissioned Flaherty to make a similar record of Samoan life. Though unfamiliar with this South Seas culture (his specialty was the Great White North), Flaherty put together 1926's Moana; this was the film for which the word "documentary" was coined by British critic John Grierson. Moana was not a success, suggesting to Hollywood that Nanook had been a fluke. When engaged by MGM to make White Shadows on the South Seas in Tahiti in 1928, Flaherty found himself butting up against the highly organized studio system--and if there was anything Flaherty was not, it was highly organized. Flaherty handled only the documentary sequences, while W. S. Van Dyke was assigned the dramatic scenes; when Flaherty proved too slow for MGM's taste, Van Dyke took over the production completely. Flaherty's next project, the South Seas-based Tabu, was likewise a collaboration, this time with director F. W. Murnau. Again, Flaherty withdrew (the problems this time were monetary rather than artistic), but when released in 1931, Tabu was heralded as a Flaherty-Murnau production.

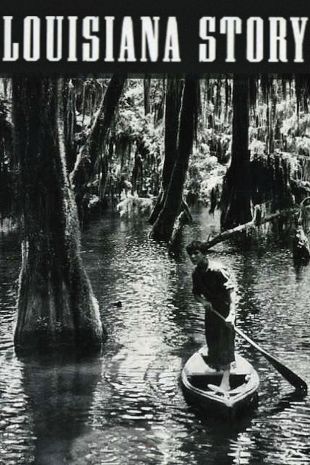

Working solo on his next project, the Irish-filmed Man of Aran (1934), Flaherty went back to his catch-as-catch-can, "take your time" production technique. He went on to direct exteriors for Alexander Korda's Elephant Boy (1937), and produced and directed two subsequent "sponsored" documentaries: The Land (1942) for the Department of Agriculture, and Louisiana Story (1948) for Standard Oil. After Flaherty's death in 1951, his wife Frances (daughter of Michigan geologist Dr. Lucien Hubbard) was the flamekeeper for her husband's memory, organizing reissues of his work for college seminars and lecture tours. One of the first presentations of the National Educational Television service (the forerunner of PBS) was a 13-week retrospective, Flaherty and Film.