Born in 1901 in Sukagawa City, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, Eiji Tsuburaya lost his mother when he was three years old and was raised by his father and an extended family who included his grandmother. By age ten, he'd become fascinated by movies and, according to a well-known story, he pilfered money from his father's store to buy a second-hand movie projector that he had seen. But, realizing that he would never be able to explain having the projector, he took it apart and saw how it was made, then destroyed it and built one from memory on his own. The family was reportedly so astonished by his ingenuity that the theft was overlooked. Tsuburaya's other great boyhood passion was aviation. He soon outgrew his fancy for flight, however, in his teens. At age 14, Tsuburaya enrolled in a flying school, only to see the institution closed down the following year. He then decided to become an electrical engineer, and, in order to pay for the needed education, he went to work for a Tokyo-based toy company.

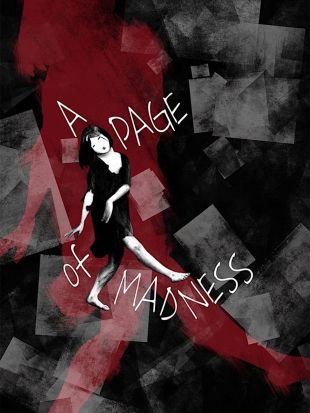

In 1919, Tsuburaya entered the Japanese film industry as a camera assistant and spent his first few years learning the technical aspects of his craft -- most importantly the special-effects processes that then existed. Based primarily in Kyoto, he moved between different studios until 1925 when he joined Shochiku. There he worked with legendary filmmaker Teinosuke Kinugasa, serving as an assistant cameraman (credited as Eiichi Tsuburaya) on the director's renowned A Page of Madness (1926). He also earned his first credit as a chief camera operator (cinematographer) on Baby Kenpo (1927). Over the next few years, in between his photographic duties, Tsuburaya started developing his own approaches and devices for photographic effects. He first had the opportunity to use some of these shooting techniques while shooting Princess From the Moon, utilizing a detailed miniature model of the city of Kyoto, super-imposed images, and forced perspective, all to startling effect. He introduced a new system of rear-projection photography for The New Earth (1937), and in 1939, he was appointed to head the newly organized special-effects department at Toho Studios.

Tsuburaya showed off his expertise in the 40 movies he worked on during the war years, most notably in his skill to realistically create great battles in the studio. He achieved particularly great notice for his work on The War at Sea From Hawaii to Malay (1942), which told of battles from the Japanese perspective and earned Tsuburaya the Japanese film industry's equivalent of an Academy Award. The end of the war led to the only major interruption of Tsuburaya's career, and, indeed, his virtual eclipse as an artist through a combination of occupational restrictions by the American administration and the instability of Toho's internal politics.

Tsuburaya endured years of hard financial times until he was finally rehired by Toho as a freelance employee in 1950. With the end of American occupation, censorship restrictions on films were eased, and in 1953, Tsuburaya worked for the first time with director Ishiro Honda on the period drama Eagle of the Pacific, a story about Japanese carrier pilots during the Second World War. The following year, they worked together on Farewell Rabaul (1954). By that time, Honda and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka were planning a movie unlike any ever made in Japan (or anywhere) before, loosely inspired by the true story of a Japanese fishing boat whose crew is exposed to radioactive fallout from an American hydrogen bomb test, resulting in death for one of them. The emerging film from this effort, Gojira (1954), marked his comeback. The stark, neo-realist style science fiction film depicts a gigantic, irradiated dinosaur and its destruction of Tokyo and the surrounding area; it was startling in its vivid representations of devastation.

In Godzilla Raids Again (1959) (aka Gigantis the Fire Monster, 1955), Tsuburaya got to repeat and expand his effects work, this time with very extensive scenes shot from the air: the destruction of Osaka and eerie shots of Godzilla and another giant creature, Anguirus, on a remote and desolate island. Indeed, in that movie the effects were even more important; however, the film was so rushed that the production and special effects seemed less impressive than those from the first movie. During the second half of the '50s, Tsuburaya suddenly became one of the busiest men on the Toho lot, and over the next 15 years, he designed and supervised the special effects for 56 movies. By the '60s, he'd achieved huge personal renown in Japan as Toho's burgeoning creative mind in science fiction and began developing an enormous fan base. Additionally, as more of his movies were released in America and other overseas markets (beginning with the recut and reshot version of Gojira, released as Godzilla, King of the Monsters in 1956), Tsuburaya's work attracted the first international following of his career, despite the fact that credits on English-language prints of these movies were often less than complete.

Tsuburaya directed and designed the special effects on movies in every genre, including a return to wartime subjects on films such as I Bombed Pearl Harbor (1961), Retreat From Kiska (1965), and Admiral Yamamoto (1968), but it was the studio's science fiction releases that made his reputation -- not just the Godzilla films and their subsequent related offshoots, Rodan and Mothra (the first Japanese monster movies done in color), but films such as The Mysterians (1957) and the science fiction-crime hybrid thrillers The H-Man (1958), Secret of the Telegian (1960), The Human Vapor (1960), and the serious topical anti-nuclear drama The Last War (1961). All of these movies make for fascinating viewing, even though none of them received any respect from critics.

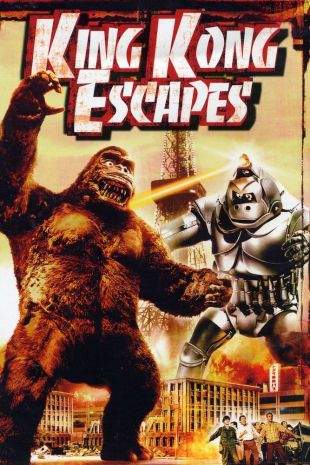

In the midst of these popular creations, Tsuburaya also worked on such critically acclaimed international releases as Akira Kurosawa's Throne of Blood (1957) and Hiroshi Inagaki's Chushingura (1962). In 1963, he founded Tsuburaya Productions, a television company of his own. The studio made its debut two years later with the series Ultra Q, which was a hit on Japanese television. A year later came Ultraman, the first incarnation of a giant-sized hero, which delighted audiences over the next three decades. Ultraman was not only successful in Japan, but was among the earliest live-action Japanese series to be exported around the world. Tsuburaya continued to divide his time between television and films for the next few years, working on such movies as Destroy All Monsters and Godzilla's Revenge, while also serving as executive producer for Ultraman. In his late sixties, he was still one of the busiest men on the Toho lot and he never slowed down, continuing work on Honda's Latitude Zero (1969) and Seiji Maruyama's Battle of the Japan Sea (1969). According to Godzilla scholar Steve Ryfle in his book, Japan's Favorite Mon-Star, Tsuburaya had also been selected to be creative director of the Mitsubishi exhibit at the 1970 Osaka World's Fair, but he never followed through on that project.

On January 25, 1970, while vacationing in Shizuoka Prefecture, Tsuburaya suffered a sudden, fatal heart seizure. Following his death, his influence was felt indirectly on Toho for decades. His successor as head of the studio's special-effects department, Koichi Kawakita, had been one of Tsuburaya's employees at Toho and had also directed Ultraman in the early '70s. His company continues to thrive more than 30 years later. Tsuburaya Productions operates under the direction of his grandson, Kazuo Tsuburaya.