Georges Méliès, the most significant creative artist of very early motion pictures, was born the third son of a wealthy Parisian bootmaker. After a stint in the French Army, Méliès went to London to apprentice in the shop of a friend of his father's. Méliès' English was poor, so he began to take refuge in the Egyptian Theater, an establishment run by the English magicians Maskelyne and Cooke. By the time Méliès returned to Paris in 1885, he was hooked on magic and determined to become a conjurer himself.

At first, Méliès attended to his father's factory equipment, but, in 1888, the elder Méliès retired, and Georges sold his interest in the family business in order to buy the long-abandoned Theatre Robert-Houdin in Paris. In December 1895 he was invited to attend the first screening of the Lumière Cinématograph and was determined to have one for his own theater. The Lumières weren't interested, but Méliès obtained a pirated Edison projector through R.W. Paul in London. Through studying this machine, Méliès and a mechanic named Lucien Koster built a motion picture camera of their own, and Méliès made his first films in May 1896, establishing himself as the Star Films brand with Koster as partner. In Méliès' 70th short film, The Vanishing Lady (November 1896), he stopped the camera deliberately in order to replace a woman behind a veil with a skeleton. This film literally represents the very birth of special effects photography in motion pictures. Méliès had a name for it, truc d'arrêt, or artificially arranged scenes.

In December 1896, Méliès made the first horror film, The Devil's Castle. Already many of Méliès' key elements are in place; a huge bat turns into Satan, a beautiful lady emerges from a smoky cauldron, ghosts and witches frolic about. In March 1897, Méliès completed construction of a movie studio, the first in Europe. He then embarked on making reconstructed newsreels of news events in addition to his magical subjects. One such "newsreel," The Dreyfus Affair (1899), was laid out in 12 scenes and may have been the first film to maintain a single story line over several shots. Also in 1899, Méliès began to add hand-painted color to special subjects and by the end of the century had attempted to make sound films. By 1901 he was utilizing editing to tighten scenes and punch up effects; Méliès was way ahead of his American colleagues in this regard. Méliès used specially built platforms to create the illusion of enlarging objects (The Man With the Rubber Head, 1901), in-camera matting to create multiples (The Music Lover, 1903), created superimpositions, built sophisticated models, such as an exploding volcano in The Eruption of Mount Pelee (1902), and developed countless other technical innovations. However, the true magic in Méliès' films was their charm; his use of dancing girls and acrobats as fairies and demons, his eye-popping hand-painted scenery, fashioned after the manner of late 19th century illustration, and his own whimsical star turns as Satan, wizards, aged professors, scientists, and the like.

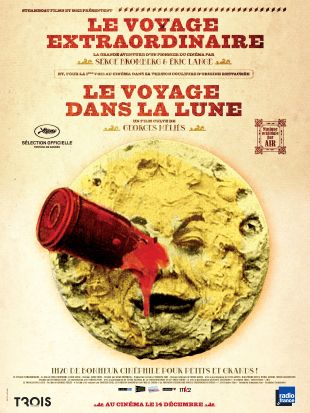

In 1902, Méliès made A Trip to the Moon, destined to become his best-known film, though not his personal favorite. Through its great popularity, Méliès learned that his films were being duplicated illegally in the United States. Méliès began to copyright his films in America and established an office for Star Film Company in New York City under the supervision of his brother, Gaston Méliès. Georges Méliès' films were particularly popular in the United States and in Britain and exercised a vast amount of influence on early American and British filmmakers. In 1904, Méliès made his masterpiece, Le Voyage à travers l'impossible (The Impossible Voyage). Told in 40 scenes and lasting 22 minutes, it was both the longest and most complex narrative film of its time.

In 1905 Méliès began to feel the heat from local competition. His films were typically shown at his own theater in between live magic acts, and they were distributed better internationally than any other French films of the era. But in France, Méliès' bread and butter was in the carnival and fairground cinemas set up in temporary structures. Competitors such as Léon Gaumont and Charles Pathé were building movie theaters in the suburbs that were intended as permanent fixtures, and Méliès was hard-pressed to compete against this new wrinkle in the industry, as the overhead on his films was incredibly high. In 1908, Méliès signed up with the Motion Pictures Patent Trust in the United States, and in order to meet their standard of "one reel a week" he had to put his own pace of production into such high gear that he could barely keep up with it. In 1908 alone, Méliès equaled his entire 1896-1907 output in terms of overall running time. By 1909, Gaston Méliès had stepped into the breach and began producing Westerns in the United States, taking the pressure off Méliès having to produce so many films. But there was a new problem at home; that year, Charles Pathé introduced a measure that restructured the pricing on films in a way that put the fairground cinemas out of business. Georges Méliès then took a needed break from filmmaking that lasted nearly two years. Upon his return in 1911, the industry had drastically changed, and Pathé distributed Méliès' final films. Charles Pathé viewed Méliès as a carny who was always putting the cause of "Art" above that of commerce, and who didn't know the value of a franc. Pathé had Méliès' final productions, such as The Conquest of the Pole, whittled down from feature length to less than half their running time. When Méliès complained and wanted out of their agreement, Pathé consented, but insisted on full repayment of all advances against production costs.

Méliès was effectively finished as a producer of films, though World War I kept his creditors at bay for a time. By 1925 he had lost his property, his studio, his theater, and his family. Méliès' wife had died just before the war, so he remarried to Jeanne D'Alcy, an actress from earlier days. Together they eked out a miserable existence working in a kiosk at a railroad station. In time, Méliès was rediscovered and hailed by the Paris Surrealists as a pioneer surrealist artist. By the time of his death, Méliès' basic needs were met, and something of his reputation, and self-esteem, was restored.

Georges Méliès was the first master filmmaker. Though most of his films are a century old and counting, they still serve as a source of delight and wonder. At their first revival in 1929 only eight Méliès films could be found of the 512 subjects he made; in the year 2001, through the worldwide cooperation of film collectors and archives, more than 200 titles are extant and more are being found. Each new title found is of unique interest, as no filmmaker in history had more to say about demonology, mythos, and the spirit world than Georges Méliès, the father of cinematic horror, fantasy, and science fiction.