K. Gordon Murray is a name that will get a flash of recognition from many Americans born between 1950 and 1966, though they might not know exactly why they recognize it. Murray made his mark as a film distributor, specializing in children's movies, and he was so successful that at one point he had eclipsed Disney as a source of children's films.

Kenneth Gordon Murray was born in Bloomington, Illinois. From his teens onward, he was involved with carnivals and circuses -- which also extended to illegal bingo and slot machine operations that he would set up in fly-by-night casinos in tents outside medium-sized towns and cities. From there, he moved into the exploitation movie business through his licensing of films owned by legendary exploitation mogul Kroger Babb. In the late 1950s, Murray also began working two other angles of film programming: horror pictures and children's films. He purchased a series of mostly Mexican-made movies in both genres, re-scripting them and dubbing them in English from a studio in Coral Gables, FL, with a small group of writers and voice actors.

And it was here that Murray's special style began taking hold. The horror films that he'd purchased each had a distinctive look, mixing familiar genre elements with unfamiliar foreign variants. Most of the Mexican horror pictures -- all black-and-white -- were modeled roughly after the Universal-style chillers (especially the "B" films) of the late '30s and early '40s, trying for an appearance of elegance in the costuming, and utilizing forbidding, cavernous settings. The children's films had their own odd yet attractive look, taking well-known figures out of fairy tales and popular mythology and presenting them (in color) in strange, distinctly non-Hollywood settings, mixing them with exotic elements derived from their south-of-the-border origins. Murray soon began buying German-made fairy-tale films, also in color, and began preparing them for U.S. release.

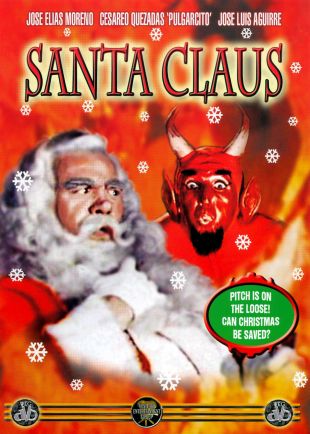

The children's films proved to be Murray's key to fortune in the 1960s. He would book the movies in select theaters or theater chains in specific territories that would show them exclusively as Saturday and Sunday matinees. The theater owners would get a flat fee, and Murray's company would claim all of the receipts. He would saturate the area with television and newspaper advertising and all kinds of specialized ballyhoo -- such as getting actors made up as a monsters or other characters from the films to appear at the theaters and pose for the local newspapers -- for weeks ahead of time to promote the event. The budget for advertising these films in the various chosen markets would far exceed the amount of money spent on the dubbing and licensing -- even on the making of the movies by their original producers. The children's films were also advertised heavily in theatrical trailers that emphasized their songs, dance numbers, and fantasy settings. The inevitable result was that thousands of children and their parents filled the theaters' seats.

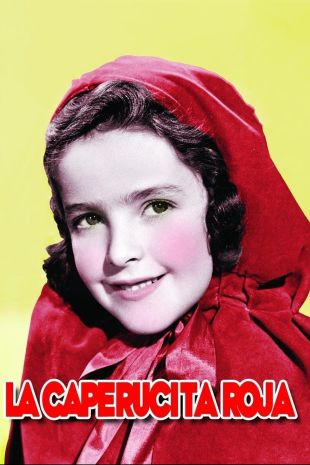

Murray made a fortune off movies such as Santa Claus, Puss 'n Boots, Little Red Riding Hood (and its sequels), and Rumpelstiltskin, and in doing so created his own marketplace: the kiddie matinee. It was a marketplace that he effectively owned for much of the 1960s. A few enterprising distributors had previously tried reviving older movies in matinee programs aimed at children and their parents, but Murray created an ongoing business with his movies, often running them in conjunction with various holidays. He was so successful at it that he was approached by one of the television networks about doing a weekly half-hour fantasy series. He never brought that off, but from 1960 until the second half of the decade, Murray's name was as prominent as Disney's as a source of children's entertainment.

The horror films worked out a little differently, and not quite as well, though they were still profitable and earned him a unique place in that genre's history. He was never really able to sell them successfully in theaters, despite heavy efforts at promotion and some primitive trailers, which made even the worst of them look more interesting than they were. While some of the monsters took the form of well-known apparitions such as werewolves and vampires, and a familiar face such as Lon Chaney Jr. showed up once in a while, many others were unique to their respective films and the culture that had generated them: mummies that transformed into bats and other creatures; brain-sucking reanimated corpses; and a few offbeat variations on Hollywood-spawned creatures, such as "Frankensteen" (pronounced that way) and a killer resembling a young Boris Karloff. Perhaps the best of these movies was The Curse of the Doll People, in which a reanimated doll wanders around stabbing people. These movies didn't do much business in theaters, despite overheated efforts at hype, promising such thrills as "Hypnoscope." Fortunately for Murray, he had the television rights sewn up as well, at a time when local stations were hungry for horror and science-fiction programming to fill out their weekend schedules. What's more, most of those stations didn't care if the horror movies were in color or black-and-white, as they were still mostly broadcasting in black-and-white. Murray was able to license packages of these pictures to an array of stations, some of them network owned and operated -- WABC-TV in New York, for example, ran Doctor of Doom and Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy, a pair of movies featuring Las Luchadoras, a lady wrestling tag-team, on Saturday afternoons.

By the end of the 1960s, the audience for Murray's children's films had begun to disappear. As kids became more sophisticated; fairy-tale characters couldn't compete with such TV creations as the Archies, Scooby Doo, or Josie & the Pussycats. Murray had always kept his hand in actual filmmaking, and he attempted to generate some short children's movies that utilized characters seen in the Little Red Riding Hood films -- perhaps in the hope of coming up with some Disney-type franchise characters -- but these efforts failed. Oddly enough, even amid the success of his children's pictures, he had never quite walked away from the exploitation market. In 1967, he produced Shanty Tramp, a picture about rural immorality. He later made Savages From Hell (1968), The Daredevil (1972), and Thunder County (1974) -- the latter starring Mickey Rooney, surely the most prestigious acting name ever associated with one of Murray's movies -- before leaving the movie business in the mid-'70s. By then, he was making most of his money from Florida real estate, prospering even more than he had from his movie ventures. Murray died on December 30, 1979, of a heart attack.