Karl Hartl occupies two special places in cinema history: one in the world at large as an artist of great stature during the mid-20th century, and the other in his native Austria as one of the country's most important filmmakers during that period, as well as one of its anti-Nazi patriots during World War II. His decision to stay in Germany (and then Austria) during the Hitler era kept him from gaining the recognition in America enjoyed by Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, and other German and Austrian exiles, but it allowed him to make an important contribution to his homeland, as a patriot and quiet resistance leader during the dark years.

Born in Vienna in 1899, Hart began working at the Sascha Film Factory during World War I, when the company was short of workers. By 1919, Hart was working as an assistant director, and helped produce The Prince and the Pauper (1920), Masters of the Sea, A Vanished World, and Samson and Delilah (all 1922). Hartl became a director in his own right in 1930 with A Student Song from Heidelberg. Following the comedy The Prince of Arcadia, Hartl took on F.P. 1 Doesn't Answer (1933), a tale of espionage and romance surrounding the construction of a gigantic airplane landing platform in the middle of the Atlantic. Made at Berlin's UFA Studios, the movie was done with three different casts -- one German (led by Hans Albers), another English (led by Conrad Veidt), and another French (led by Charles Boyer) -- all directed by Hartl. For a change of pace, Hartl's next film was an adaptation of Ralph Benatzky's operetta Her Highness, the Saleslady (for which he also did a French version), assisted by 26-year-old Henri-Georges Clouzot. Then it was back to science fiction with the futuristic thriller Gold in 1934. Shot on a grand scale with extraordinary sets, the movie captured the imagination of millions of filmgoers with its tale of a scientist's pursuit of modern alchemy. The movie's cutting-edge scientific orientation resulted in its subsequent suppression by the Nazi-era government, which tried to seize and destroy every known print.

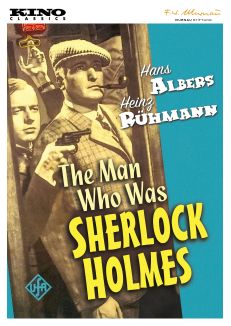

Hartl was able to work in Germany after the rise of Hitler and did his best to keep politics out of his films with Der Zigeunerbaron, Die Leuchter des Kaisers, Ritt in die Freiheit, and Der Mann, der Sherlock Holmes War. Hartl had hoped to crown his comedic achievements the following year with a series of movies starring the celebrated leading man Hans Albers and a historical spoof called Casanova, but the German takeover of Austria in the spring of 1938 forced him to abandon the film. It was at this point that fate intervened in a most unexpected way in Hartl's career, when the German propaganda ministry announced the formation of Wien-Film, a production unit that would make movies on behalf of the Third Reich and its propaganda requirements -- and they wanted Hartl to head the studio. He hesitated, but was persuaded by his colleagues, who were fearful that if Hartl didn't accept, the ministry would send in a dedicated Nazi to take charge. Thus, Hartl felt forced to accept the offer to head the group.

Hartl ended up running Wien-Film for almost seven years, keeping productions centered on Austrian history and Viennese themes. He managed to put the propaganda films demanded by Berlin on the back-burner for years, claiming substandard scripts had been provided or that the necessary actors or technicians were unavailable, or the needed facilities were in use, though some propaganda films were produced. On the whole, Hartl made sure that the movies produced during his tenure had their subjects buried safely in the pre-Nazi, un-German, Viennese past before the 20th century -- costumed romances set in the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ironically, these very attributes made the resulting movies quietly political and turned Wien-Film under Hartl into a focus of quiet anti-German resistance.

During his entire seven years in charge of production, the only movie that Hartl himself directed was Wen die Götter Lieben (aka Whom the Gods Love, 1942), a biographical film about Mozart that he had to take over from the stricken original director. All of his quiet work resisting the Nazis from within served Hartl and Vienna well after the war, when he was permitted by the Allied occupation authorities to remain in charge of Wien-Film. The division of the city into four separate zones made it impossible for the company to produce much, however, and he left the job soon thereafter. His first postwar movie was Cavalcade (1948), a story of a century of Austrian history as seen through the lives of members of a Viennese family. He was soon at the top of his profession, drawing together the best cinematic and theatrical talents in the city for films such as Der Engel mit der Posaune. That movie was regarded with pride by Austrian critics, who saw in its creation the salvation of their national film industry's prewar/pre-Nazi quality. It was also sufficiently impressive to get Hartl an invitation from his old friend Alexander Korda -- now a knight of the realm in England -- to make an English-language version in London. It was all a little like the old days of making simultaneous versions of the same movie with German, French, and English casts. The resulting film, The Angel With the Trumpet, which co-starred Maria Schell and Oskar Werner in their first international roles, was successful enough to lead Hartl to make an Anglo-Austrian movie, The Wonder Kid, at the outset of the 1950s.

Hartl returned to making movies in Germany in 1952 with Haus des Lebens (aka House of Life) and two subsequent movies. One of them, Alles für Papa (aka Everything for Daddy, 1953) starred Curd Jürgens in the days prior to his emergence as an international star. Hartl's wife, Marte Harell, was also a major star of German films during this same period. From 1954, the director was back in Austria, where his last major movie was Mozart -- Reich Mir die Hand, Mein Leben (1956), his own production of a Mozart biographical film, which supplanted his wartime effort on the same subject. By that time, however, German cinema was dominating the marketplace even in Vienna and setting the tone for all German-language film productions, a situation with which Hartl grew increasingly less comfortable. His remaining career was confined to a tiny group of movies aimed exclusively at the Austrian market, including the Swiss historical epic Wilhelm Tell (1961), on which he served as artistic supervisor. He was also the editor and designer of the documentary Flying Clipper (1962).

Hartl was largely retired in the final 15 years of his life, revered in his native Austria and beloved in the German-speaking world, though almost completely forgotten elsewhere. Of his two renowned science fiction films, F.P. 1 Doesn't Answer has been little shown outside of England since the early '80s, while Gold has all but disappeared. Ironically, its dazzling climactic scenes in the huge laboratory become much more familiar through their use by producer Ivan Tors in his 1953 sci-fi thriller The Magnetic Monster. Hartl's films of various operettas are his other international legacy, beloved of aficionados of that musical genre.

In 1978, his beloved Sascha Films, where he'd spent so many years -- and which had receded to the production of small-scale light entertainment movies, mostly for the German-speaking market, since the end of World War II -- produced its first major film in decades, A Little Night Music. The Harold Prince-directed movie, based on Stephen Sondheim's hit stage musical, and co-starring Elizabeth Taylor, Diana Rigg, and Len Cariou, opened on six continents, the first Sascha release since the 1930s to be seen across the globe. It also proved to be a swansong for the studio on the world stage, in the same year that the man who protected and preserved it from the Nazis left this Earth. Hartl died in 1978 in Vienna. He was 79.