Karl W. Freund was born in Koniginhof, Bohemia, in what later became Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), in 1890. He entered the film industry as a projectionist in 1907, but his interests lay in the other end of the business and the lens, and a year later he joined the Berlin branch of Pathé Films as a newsreel cameraman. He spent the next six years as a newsreel photographer, until he encountered a brief interruption with the outbreak of the First World War. However, even at the relatively young age of 24, he carried a substantial girth that made him unsuitable for military service; 90 days after being called up, he was a civilian again, and back working in movies. Even during this early phase of his career, Freund displayed an adventurous nature within his profession and a fascination with technological advances that put him at the cutting edge of cinematography.

Freund joined Germany's Universum Film Aktiengesellschaft (UFA), and was involved with such notable productions as Richard Oswald's The Arc (1919), during which he met the actress Gertrude Hoffman, who would become his wife. That same year, Freund worked for the first time with directors Fritz Lang (Spiders, Part 1), Ernst Lubitsch (Rausch), and F.W. Murnau (The Blue Boy, aka Emerald of Death). All of these films were well photographed, but there were a handful on which he distinguished himself sufficiently to begin attracting an international reputation -- among them were Der Golem (1920), co-directed by Carl Boese and Paul Wegener, and Murnau's The Last Laugh (1924).

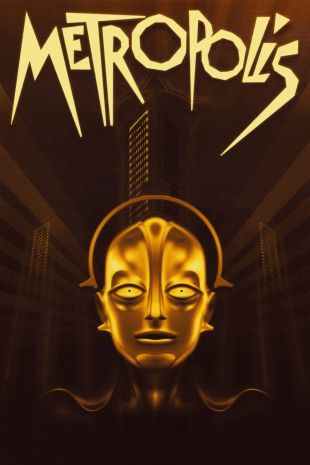

Freund also made a unique contribution to the visual style of Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927); but it was somewhat overshadowed by his work during that same period on a movie that would overwhelm much of the cinematic world with its impact, visual and thematic: Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Freund's contribution to the movie's success was immense, many of its visuals and its overall look so striking that its impact across the decades that followed only seemed to increase with time, this despite the fact that it was not that big a success at the box office in 1927-1928.

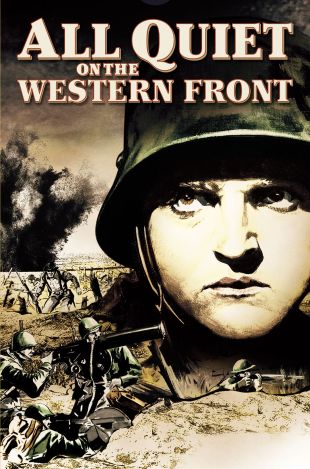

The coming of sound only enhanced Freund's career and reputation, thanks to his fascination with technical innovation. He was among the very first cinematographers to work with sprocketed magnetic tape as a sound medium, during a period in which several methods were competing for primacy, and which became the standard means of shooting sound film for the next 60 years. He was also involved with experimental color film shooting in England at the end of the 1920s. He might well have made his career in England, but Hollywood beckoned -- in 1930, he was signed to Universal, where his first project moved him into the director's chair. Freund had two directorial credits in Germany during the early '20s, for Der Tote Gast (1921) and Der Grosse Sensationsprozess (1923), but otherwise had spent the rest working from the camera. Despite his relative lack of experience, however, Universal turned over to him the task of overseeing the reshooting of the denouement of its biggest production of 1930, Lewis Milestone's All Quiet on the Western Front, which had run into serious problems in its previews and was due to open in just a few weeks.

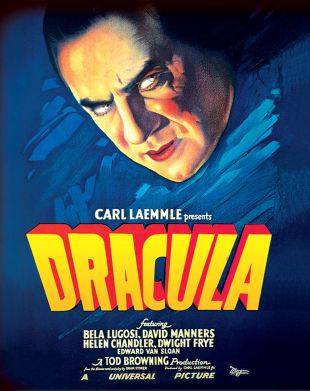

That assignment only removed Freund temporarily from his cinematography duties, however, and over the next two years he busied himself photographing such movies as Tod Browning's Dracula (1931), John M. Stahl's Strictly Dishonorable (1931, from a script by Preston Sturges), and Robert Florey's Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). That same year, he made an official return to the director's chair on The Mummy (1932), starring Boris Karloff and Zita Johann. Widely considered among the best of the early Universal horror films, the movie has held up amazingly well across more than 75 years.

Soon after this horror classic, he took the director's chair for what might arguably be the most extraordinary and unexpected film of his career, Moonlight and Pretzels (1933). A delightfully topical musical romp inspired in part by Lloyd Bacon's (and Busby Berkeley's) 42nd Street and shot in the summer of 1933 at the Astoria Studios in New York, the film combined songs and dances, the drama of backstage romance, backbiting, and double-dealing, and an amazing closing production number that encompassed images seemingly derived from Metropolis, with the overall look of a German expressionist classic. It was one of the most visually striking and finely paced musicals of its period (with very effective comedy as well), but ended up all but forgotten after its successful original run. However, Moonlight and Pretzels was a big hit anew in 2007, when it ran as part of a musical retrospective at New York's Film Forum. Freund's remaining directorial credits were confined to the next two years of his career, and showed him ranging freely between drama, light romantic comedy, and horror, closing out his director's career in the latter genre with Mad Love (1935), starring Peter Lorre.

By that point, Freund had moved to MGM, where he contributed to numerous films, often in very specialized sequences such as the rooftop production numbers in The Great Ziegfeld (1936). He photographed such classics as The Good Earth (1937, for which he won an Oscar) and Golden Boy (1939), the latter at Columbia Pictures under director Rouben Mamoulian. He remained busy at MGM throughout the war, working on some of the studio's most prestigious productions, including Tortilla Flat (1942), A Guy Named Joe (1943), and The Thin Man Goes Home (1944). In 1942, he managed to get parallel Oscar nominations, for The Chocolate Soldier and Blossoms in the Dust, in the black-and-white and color categories, respectively. He moved to Warner Bros. in the late '40s, where his work included John Huston's Key Largo (1948) and Michael Curtiz's Bright Leaf (1950). Freund closed out his movie career by photographing Montana (1950), starring Errol Flynn.

In 1951, he was approached by Desilu, a new television production company founded by the married acting couple of Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball, who were about to embark on a situation comedy series of their own. They wanted to deliver a quality product to their sponsor and their network, CBS, that was funny, but also attractive visually. Freund developed what became known as the three-camera method for shooting a television program on film in an affordable way. I Love Lucy, when it went on the air, was the best-looking series ever seen on television up to that time, and the process subsequently became the standard method of shooting series. It was their pioneering use of the process that turned Desilu into a powerhouse in the field of television production, and positioned them eventually to become a key addition to Paramount Pictures' holdings.

Freund also supervised the photography on Our Miss Brooks and December Bride, which were very popular in the early to mid-'50s. In 1955, his work at Photo Research Corp. was honored with a special technical award from the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences, for his design of the direct-reading light meter. He also represented the United States at the International Conference on Illumination in Switzerland. In 1960, after a decade as the most important and influential photographer in television, Freund retired at the age of 70, though he continued to work at Photo Research well into the 1960s. He passed away in 1969 at the age of 79 in Santa Monica, CA.