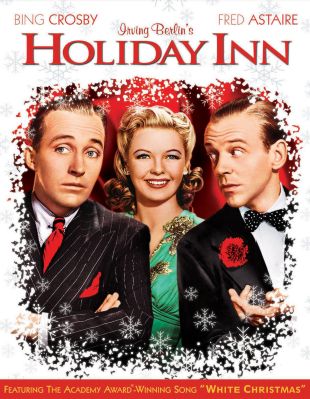

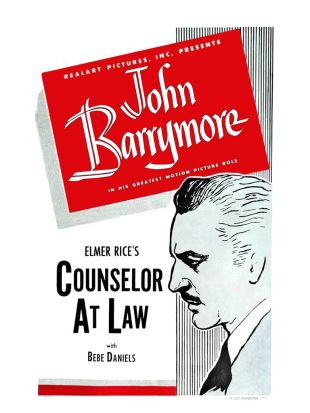

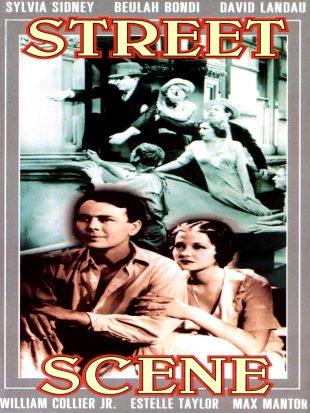

From 1914 until the mid-'40s, Elmer Rice was one of the most prominent playwrights and theatrical directors in America, and made important contributions to motion pictures, both as an author and screenwriter. Born Elmer Reizenstein in New York in 1892, he was a high school dropout who developed an interest in the legal profession and graduated cum laude from New York Law School at age 20. In 1913, the same year that he was admitted to the bar, Reizenstein decided to try his hand at writing plays: The result was On Trial, a courtroom drama that he presented unsolicited to a producer and which proved good enough to get produced on Broadway, where it was a hit, running for a year (considered a very successful run in those days) and earning its author 100,000 dollars. On Trial was also acclaimed as an innovative masterpiece for its pioneering use on-stage of a device that had previously only been utilized onscreen, the "cutback" -- that is, interrupting the action at hand to present prior events to the audience. It was following the completion of the play's run that Reizenstein -- reportedly weary of having his last name misunderstood over the telephone -- decided to shorten it to Rice. On Trial was subsequently adapted into at least three separate film versions, in 1917, 1928, and 1939. Rice, however, considered it nothing more than "a shrewd piece of stage carpentry," and spent the next nine years studying drama intensely, including a period at Columbia University under noted teacher Hatcher Hughes, experimenting with different techniques and ideas. He wrote several student works and one play, Wake Up Jonathan (co-authored with Hughes), that made it to Broadway. After a failure with It Is the Law, he wrote The Adding Machine (1923), a strange, expressionist play about a lifelong office worker, Mr. Zero, who loses his job to the device of the title, murders his boss, is tried and executed, and ends up in heaven operating the very device that cost him his job, until he is returned to earth. The play only ran nine weeks, but The Adding Machine has remained a widely studied and performed piece in drama courses for generations since, right into the 21st century. Rice went out to Hollywood for a time, generating two screenplays, Doubling for Romeo and Rent Free, as well as seeing one of his plays, For the Defense, turned into a film, but he later described that first experience of Hollywood as utterly demeaning. He collaborated in the mid-'20s with Dorothy Parker on Close Harmony, also known as The Woman Next Door, and with Philip Barry on Cock Robin, a murder mystery set backstage at a theater. In 1928, after a string of failures, Rice wrote the play for which he is most famous, Street Scene. A tragic tale set in a New York tenement, Street Scene spoke in the voice of the people, complete with vicious racial and ethnic slurs and raw hatreds on display, all couched in a hauntingly lyrical theatrical framework. It was a gritty, earthy work, utterly unlike the comedies, musicals, and upper-crust romantic stories that dominated theater in those days (and which Rice abhorred). The play was also rejected by virtually every producer on Broadway until William A. Brady agreed not only to mount it, but also to allow Rice to direct it himself. Rice's most fully realized work, the play as staged by its author used its tenement building set and backdrop as virtually a major character itself, woven into every aspect of the action, a novel element in this startlingly piercing work. Street Scene won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1929, and Samuel Goldwyn subsequently purchased the film rights and assigned it to King Vidor to direct. The 1931 Vidor movie version, based on Rice's own screen adaptation, utilized a huge set the size of a city block that gave the screen drama a subtly enveloping quality (almost disposing of the boundaries of the screen). Several of the stage production's original players (including John Qualen, Matt McHugh, and Beulah Bondi) also appeared in the movie, and it remains one of the best screen adaptations ever done of a theatrical drama, and also one of the most watchable of early talkies. During the two years between Street Scene's original theatrical run and Goldwyn's film version, Rice saw his unsuccessful play See Naples and Die brought to the screen as Oh Sailor, Behave in 1930. Street Scene started a new trend in theater, paving the way for works such as Sidney Kingsley's Dead End (which was also filmed by Goldwyn) and Clifford Odets' Rocket to the Moon and Golden Boy. The playwright's next major successes were The Left Bank, a barbed look at the self-styled expatriate American bohemians living in Paris, which was written after an extended trip to Europe, and Counsellor-At-Law, a drama about a successful Jewish attorney who finds his personal life and career shattered. Both were also produced and directed by Rice and were hits on-stage, with Counsellor-At-Law proving especially durable in a revival a decade later. With Rice again providing the screen adaptation, Counsellor-At-Law (1933) was directed by William Wyler, and is one of that filmmaker's best works; the action is fluid yet tense, and held entirely within the confines of a single large set of a law office in a New York skyscraper, yet one never feels "confined" by the film. 63 years later, in 1996, during the run of Christopher Plummer's Barrymore show on Broadway, the film Counsellor-At-Law was presented to nearly full houses during a day-long run at New York's Film Forum, as the best extant specimen of the real Barrymore's art. Rice's subsequent stage efforts, alas, were notably less successful, steeped as they were in fiercely topical and political subject matter (and carrying titles such as We, the People, that hardly evoked entertainment) that Depression-weary audiences sought to forget about. The failure of his play Between Two Worlds led Rice to attack Broadway and, especially, the tastes, respective agendas, and goals of the critics assigned to cover theater, which resulted in his abandoning the New York stage for a time in favor of London. Ironically, it was in England that one of his mid-'30s New York failures, Judgment Day, became a hit. When he returned to America in 1935, Rice was made regional director of the government-sponsored Federal Theater Project in New York. He resigned, however, after running afoul of censors when he sought to present a work called The Living Newspaper, in which current political figures from around the world, including Benito Mussolini, were portrayed on-stage. He returned to writing and producing commercial plays, but Not for Children (1935), American Landscape (1938), and Two on an Island (1939) never achieved the popularity of his earlier work. Rice's biggest success of the late '30s came not as a writer but as the director of Robert Sherwood's play Abe Lincoln in Illinois. In the early '40s, Rice took one more stab at a Hollywood career when he co-wrote the scenario (with Claude Binyon) for Mark Sandrich's Holiday Inn (1942), starring Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire, and Marjorie Reynolds, which introduced a brace of great Irving Berlin songs, including "White Christmas." He continued to write and produce plays and saw one more of his plays, the distaff Walter Mitty fantasy-comedy Dream Girl, filmed at Paramount in 1947, with Betty Hutton in the lead. Rice was still active on various theater boards in the 1960s but produced his last play, Love Among the Ruins, in 1963. His major influence had waned by the end of the '40s, apart from the perennial popularity of The Adding Machine (which was filmed two years after his death), Street Scene, and Counsellor-At-Law.

Elmer Rice

Share on