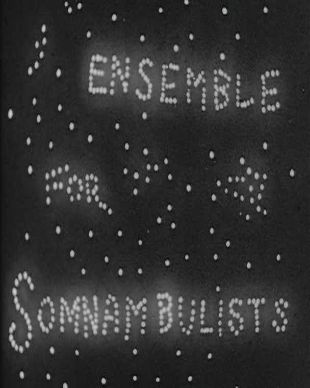

Maya Deren did not launch the American film avant-garde, but more than any of her contemporaries, she galvanized, popularized, and feminized it. Famed for her 1943 masterpiece Meshes of the Afternoon, one of the most widely viewed and analyzed of all experimental films, Deren was a tireless proponent of independent movie production and distribution, constantly writing, touring, and lecturing in support of her craft. She not only distributed her own films, but also financed her projects with the aid of fees and grants, in 1946 receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship -- the first awarded for creative filmmaking, and the first ever bequeathed to a woman. While her films lack an overtly feminist consciousness, Deren was arguably the first true woman auteur in American cinema, and her work challenged not only the medium's gender stratification but also its thematic principles, probing issues of sensuality and identity clearly distinct from the efforts of her male counterparts. And although many of Deren's films and writings drifted into obscurity following her 1961 death, her reputation has been greatly rehabilitated in later years, and her aesthetics and ethics alike remain a touchstone for independent filmmakers of all persuasions -- as the pioneering avant-garde director Stan Brakhage once said, "She is the mother of us all." Deren was born Elenora Derenkowsky in Kiev, Ukraine, on April 29, 1917. Her family fled to the U.S. in 1922 following a series of anti-Semitic pogroms, and settled in Syracuse, NY; her father, a psychiatrist, and her mother, an artist, were made naturalized American citizens in 1928, at that time adopting the abbreviated surname "Deren." While attending school in Switzerland, Deren developed an interest in writing poetry, and upon returning to New York she studied journalism and political science at Syracuse University, where she also became fascinated with filmmaking. After marrying student activist Gregory Bardacke, she relocated to New York City, continuing her education at New York University and serving as the National Secretary of the Young People's Socialist League; Deren also worked as a secretary and tour manager for the anthropologist and dancer/choreographer Katherine Dunham, credited as one of the first performers to expose American audiences to traditional Caribbean music and dance. Dunham was no doubt a major influence on Deren, who would later explore and document Haitian dance and Voudoun (voodoo) rituals in her own work. After receiving her master's degree in English literature from Smith College in 1939, Deren divorced Bardacke. While in Los Angeles with a Dunham stage production, Deren met Czech filmmaker Alexander Hammid; they later married, and she changed her given name from Elenora to Maya, from the Hindu goddess of sorcery. With Hammid's assistance, in 1943 she filmed Meshes of the Afternoon, shooting with a hand-wound Bolex camera and funding the project out of her own pocket, even appearing as its enigmatic protagonist(s). Although Deren would later criticize and renounce the surrealists, the resulting 16 mm, 14-minute effort plainly evokes the experimental approaches of Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dali, and Luis Buñuel; an elliptical, poetic meditation on the self, hypnotically edited and relying on multiple exposure imagery to foster the illusion of myriad personas, Meshes of the Afternoon is a landmark of American cinema, a brilliant examination of form, content, and technique that conjures both film noir and gothic melodrama even as it challenges the very principles of standard narrative storytelling. Also in 1943, Deren began work on Witch's Cradle, a collaboration with Marcel Duchamp intended to articulate the magical properties of objects housed in Peggy Guggenheim's legendary Art of This Century gallery. Like many of Deren's projects, the film remained uncompleted. The following year, however, she did release her second short, At Land; again assuming the featured role -- this time portraying a woman who emerges from the sea to engage in a series of social conceits, including a dinner party and a chess match -- as in Meshes of the Afternoon, Deren explored themes of identity and context, relying on complex editing patterns to articulate questions of sameness and difference. For 1945's Ritual in Transfigured Time, a further examination of female psyche and sexuality, Deren cast the dancer Rita Christiani and the writer Anais Nin, employing similarly intricate edits and slow-motion effects to transform everyday movements into choreographed, dance-like actions -- more than one historian has called Deren the first dance filmmaker, and indeed, the intricate movements of the dancer's body and the medium's relations to space and time plainly embody the recurring concerns of her cinema. 1946 was in many respects the most pivotal year of Deren's career. After several years of distributing her films to colleges and universities on her own, she booked theProvincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village to mount her first major public exhibition -- titled "Three Abandoned Films," the retrospective featured Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, and her latest effort, A Study for the Choreography of Camera. The screening was an unqualified success. Also in 1946, Deren published her book An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, and perhaps most notably won the first Guggenheim Fellowship for filmmaking. Her Guggenheim endowment funded not only her own non-profit filmmaking group, the Creative Film Foundation, but also a long-planned trip to Haiti to document her continuing fascination with Voudoun rites and dances. Between 1947 and 1954, Deren made three trips to Haiti, shooting over 20,000 feet of footage. The project yielded a book, 1953's Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, but her plans to complete a film documentary remained unrealized during her lifetime -- not a trained anthropologist, her efforts to submit her footage for use in studying and documenting the Voudoun culture were dismissed by the anthropological community. During the intervening years, Deren did complete another short film, 1948's Meditations on Violence, perhaps the least-viewed and least-discussed of her finished works; from 1949 to 1951, she also began work on no fewer than three major projects -- provisionally entitled Medusa, Ensemble for Somnambulists, and Haiku -- none of which saw completion. As Deren's attempts to complete and distribute the Haitian footage faltered, her other work slowed and suffered, but she nevertheless solidified her standing as the American avant-garde's preeminent champion, appearing everywhere from Yale University to NBC's The Today Show to further her cause. In her lectures, Deren increasingly outlined and defined her views on film theory, and at the 1953 Cinema 16 symposium "Poetry and the Film" famously advocated her belief that the medium operates on a pair of axes: a horizontal, narrative axis encompassing character and action, and a vertical, poetic axis of mood, tone and rhythm. Between 1952 and 1955, she filmed The Very Eye of Night, a collaboration with the Metropolitan Opera's School of Ballet; released in 1959, it was her final completed film. Deren died suddenly on October 13, 1961, of a massive cerebral hemorrhage, most likely brought on by a longtime dependence on medically prescribed amphetamines and sleeping pills. (Many associates and acolytes speculated she was instead the victim of Voudoun rites.) In 1973, her third husband, Teiji Ito, teamed with his future wife, Cherel Winnett, to begin assembling Deren's Haitian footage into completed form; also titled Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, it was released in 1977.

Maya Deren

Active - 1942 - 2018 |

Born - Apr 29, 1917 |

Died - Oct 13, 1961 |

Genres - Avant-garde / Experimental, Drama, Culture & Society

Share on