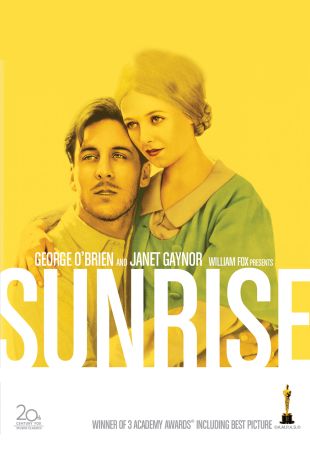

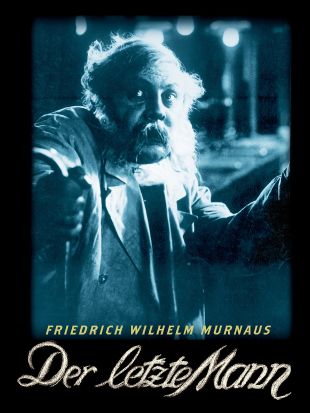

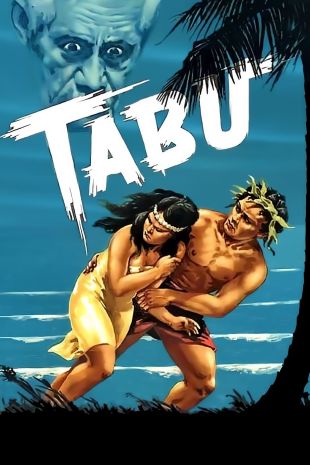

Edgar George Ulmer was one of the very few genuinely creative filmmakers who, for a time, chose the world of low-budget B-films over the more opulent milieu of mainstream, high-profile A-pictures. Born in Vienna, Austria, he worked as a stage actor and set designer while studying architecture and philosophy, and later joined the company of the legendary German theatrical producer Max Reinhardt. He first visited America in connection with a Reinhardt production, and became briefly involved with Universal Pictures in the mid-'20s. On his return to Germany he served as an assistant to filmmaker F.W. Murnau, and worked as art director on the latter's film Sunrise, which was shot in Hollywood in 1927. Ulmer went back to Germany to co-direct Menschen am Sonntag (1929) in collaboration with Robert Siodmak. He emigrated to Hollywood in the early '30s, working as a writer on movies such as Tabu and as an art director. By 1933, Ulmer had been signed to Universal as a director, making his debut with The Black Cat (1933), a bizarre and harrowing horror film starring Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, that seemed designed to startle the viewer at every turn, intermingling elements of grisly sadism and knowing black comedy. The Black Cat remains one of the more distinctive of Universal's horror films of the 1930s, and it seemed to herald the arrival of a major new talent in the genre. Ironically, it was also to be Ulmer's last movie for a major studio for 14 years. Sometime after his arrival on the Universal lot, he'd made the acquaintance of Shirley Kassler Alexander, an employee of the script department and the wife of Max Alexander, a producer at Universal and also a nephew of studio owner Carl Laemmle. The two fell in love, which immediately put her job and Ulmer's American career in jeopardy -- he directed one low-budget Western, Thunder Over Texas, under the pseudonym "John Warner" for tiny Beacon Pictures, based on one of her scripts. Soon after, she divorced Alexander and the two were barred from the Universal lot. She married Ulmer, a union that lasted until his death nearly 40 years later. In the meantime, however, the director discovered that he was effectively blackballed from the Hollywood film industry. Ulmer was forced to return to the East Coast to get any film work over the next few years. There was still a movie industry of sorts in New York. Very few talented hands from Hollywood ever made the trip east, and Ulmer, with his experience both in Hollywood and in Germany (and a hit Hollywood movie under his belt), was something of a find for anyone producing movies in New York. He, in turn, found a place where he could continue his career, making films in Yiddish for producers aiming at that audience (which was considerable, right up to the advent of World War II), and also documentaries such as the venereal disease educational/exploitation movie Damaged Lives, and, later still, movies with all black casts for the theater circuits catering to black communities. It was during this period that Ulmer began making his reputation -- with a lot of help from Shirley Ulmer as a screenwriter and script editor -- as something of a cinematic magician, who could make good ideas work on screen for very little money. Contrary to the conventional wisdom about Ulmer, that he spent his career avoiding high-profile projects and the major studios, he did have ambitions beyond the scope of 62-minute thrillers and dramas. He hoped to be hired by one of the major studios, and in 1941-1942 Paramount seemed interested -- there was apparently even discussion about his remaking The Blue Angel with Veronica Lake. In 1943, at the prompting of expatriate German producer Seymour Nebenzal, with whom Ulmer had a longstanding friendship, he approached Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), a B-studio that stood at the very bottom of the barrel of Hollywood's "Poverty Row." PRC had enjoyed two good years and was beginning to upgrade its releases under the guidance of production executive Leon Fromkess. Ulmer and Fromkess got along well, and he was able to persuade Fromkess of his ability not just as a director able to bring in good movies for very little money, but also as a production executive. As a result Ulmer was one of the major forces at PRC as well as being its top director, helping in no small way to transform the studio's output and image. He was the head of production in all but name (outside of its Western films, which were virtually a separate division), not only developing projects for himself but devising and assigning films to other directors of his choice. His own output, beginning with Bluebeard (1944), a beautifully made, lyrical, poignant, and suspenseful period drama starring John Carradine as the notorious strangler, represented not only some of the finest films of his career, but several of the most complex and entertaining B-movies of the 1940s: Strange Illusion (1945), a harrowing and piercing modern dress adaptation of Hamlet; Detour (1945), a cross-country film noir/thriller, shot in under a week for less than 20,000 dollars, that is still shown widely on television, revived regularly in theaters, and studied in film courses around the world; and The Wife of Monte Cristo, a brilliant costume swashbuckler. All of these movies, whatever their respective sources, featured screenplays written or edited by Shirley Ulmer -- all looked and played better and more memorably than movies made for ten or 20 times the money at the major studios. Ulmer remained with PRC after Fromkess' departure in 1946, but his relationship with the tiny studio ended in 1947, after he was loaned out to direct The Strange Woman at United Artists. This was Ulmer's first chance to return to working under the umbrella and auspices of a major studio in 13 years, and he welcomed it as well as the opportunities it afforded him in terms of budget, casting, and shooting. He was back on the map, however, and in 1947 he made three major films that were widely advertised, seen, and reviewed:The Strange Woman, Carnegie Hall, and Ruthless (which was released the following year). He did the unusual swashbuckler The Pirates of Capri in Italy during 1949, and then was back at United Artists in 1951 to do The Man From Planet X, one of the earliest and strangest (and most enduringly popular) of science fiction stories dealing with alien visitors. In 1951, he even returned to New York City to shoot the offbeat comedy/drama St. Benny the Dip, but most of Ulmer's movies over the next few years were more conventional in both content and production. In 1960, however, Ulmer inaugurated a series of strange, compelling low-budget science fiction films: Beyond the Time Barrier (1960), The Amazing Transparent Man (1960), and L'Atlantide (Journey Beneath the Desert) (1961), the latter a remake of a film first done in Germany in 1932 by the director's friend Seymour Nebenzal. Ulmerclosed out his career in 1965 with The Cavern, one of the more unusual World War II dramas of the 1960s or any other era. Shirley Ulmer continued to write screenplays well into the 1970s. Edgar Ulmer passed away in 1972, little remembered at the time by the public. In the decades since, however, a new generation of filmmakers, including Martin Scorsese and John Landis, has come to champion his work. Detour, in particular, has achieved considerable acclaim as a seminal example of film noir, and was picked by the Library of Congress as one of the first group of 100 films worthy of special preservation efforts, right alongside Citizen Kane and 98 other vastly more expensive, higher profile movies.

Edgar G. Ulmer

Share on